Fermi Stills

Overview

A collection of Fermi-related still images, illustrations, graphics and short clips.

2024

Fermi Mission Detects Surprising Gamma-Ray Feature Beyond Our Galaxy

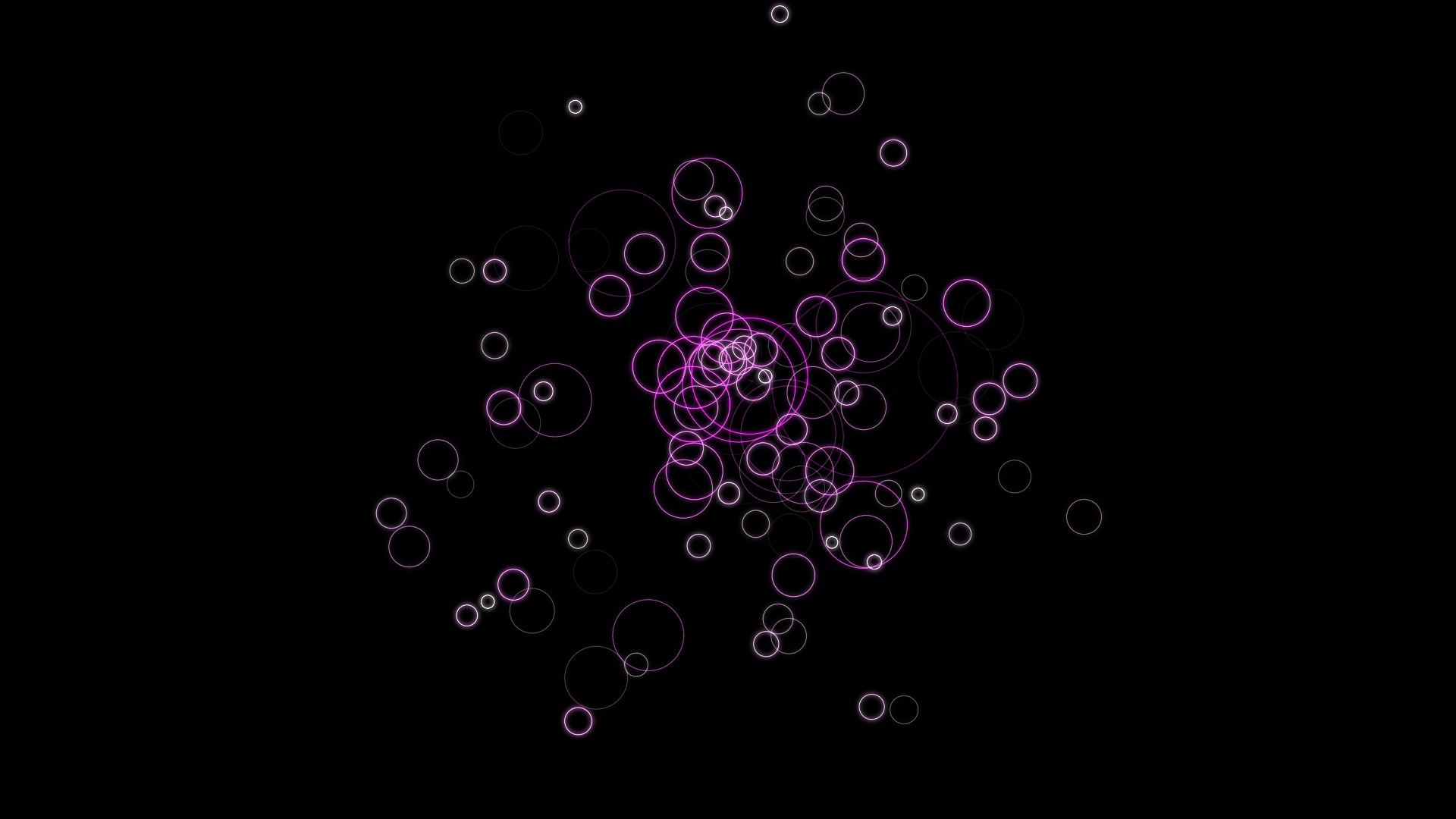

Go to this pageThis artist’s concept shows the entire sky in gamma rays with magenta circles illustrating the uncertainty in the direction from which more high-energy gamma rays than average seem to be arriving. In this view, the plane of our galaxy runs across the middle of the map. The circles enclose regions with a 68% (inner) and a 95% chance of containing the origin of these gamma rays. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center || Dark_Fermi_Dipole.jpg (3840x2160) [506.2 KB] || Dark_Fermi_Dipole.png (3840x2160) [8.9 MB] || Dark_Fermi_Dipole_searchweb.png (320x180) [57.6 KB] || Dark_Fermi_Dipole_thm.png (80x40) [5.4 KB] ||

Fermi Sees No Gamma Rays from Nearby Supernova

Go to this pageEven when it doesn’t detect gamma rays, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope helps astronomers learn more about the universe.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: "Trial" from Universal Production MusicWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || Fermi_Missing_GR_Still.jpg (1920x1080) [757.8 KB] || Fermi_Missing_GR_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [86.6 KB] || Fermi_Missing_GR_Still_thm.png (80x40) [6.5 KB] || 14522_Fermi_Missing_GammaRays_Captions.en_US.srt [3.4 KB] || 14522_Fermi_Missing_GammaRays_Captions.en_US.vtt [3.2 KB] || 14522_Fermi_Missing_GammaRays_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.0 GB] || 14522_Fermi_Missing_GammaRays_Good.mp4 (1920x1080) [110.3 MB] || 14522_Fermi_Missing_GammaRays_Best.mp4 (1920x1080) [382.1 MB] ||

2023

NASA Missions Probe What May Be a 1-In-10,000-Year Gamma-ray Burst

Go to this pageThe Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 revealed the infrared afterglow (circled) of the BOAT GRB and its host galaxy, seen nearly edge-on as a sliver of light extending to the burst's upper left. This animation flips between images taken on Nov. 8 and Dec. 4, 2022, one and two months after the eruption. Given its brightness, the burst’s afterglow may remain detectable by telescopes for several years. Each picture combines three near-infrared images taken at wavelengths from 1 to 1.5 microns and is 34 arcseconds across. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Levan (Radboud University); Image Processing: Gladys Kober || GRB_WFC3IR1108+1204_circled.gif (512x512) [3.5 MB] ||

Fermi Captures Dynamic Gamma-ray Sky

Go to this pageWatch a cosmic gamma-ray fireworks show in this animation using just a year of data from the Large Area Telescope (LAT) aboard NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Each object’s magenta circle grows as it brightens and shrinks as it dims. The yellow circle represents the Sun following its apparent annual path across the sky. The animation shows a subset of the LAT gamma-ray records now available for more than 1,500 objects in a new, continually updated repository. Over 90% of these sources are a type of galaxy called a blazar, powered by the activity of a supermassive black hole.Credit: NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center/Daniel Kocevski || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark_ProRes_3840x2160.mov (3840x2160) [170.3 MB] || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark_1600.gif (1600x900) [6.5 MB] || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark_1050.gif (1050x590) [3.2 MB] || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark.gif (800x450) [2.1 MB] || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark_4k.mp4 (3840x2160) [12.1 MB] || Fermi_LAT_LCR_Feb2022-Feb2023_Dark_4k.webm (3840x2160) [1.9 MB] ||

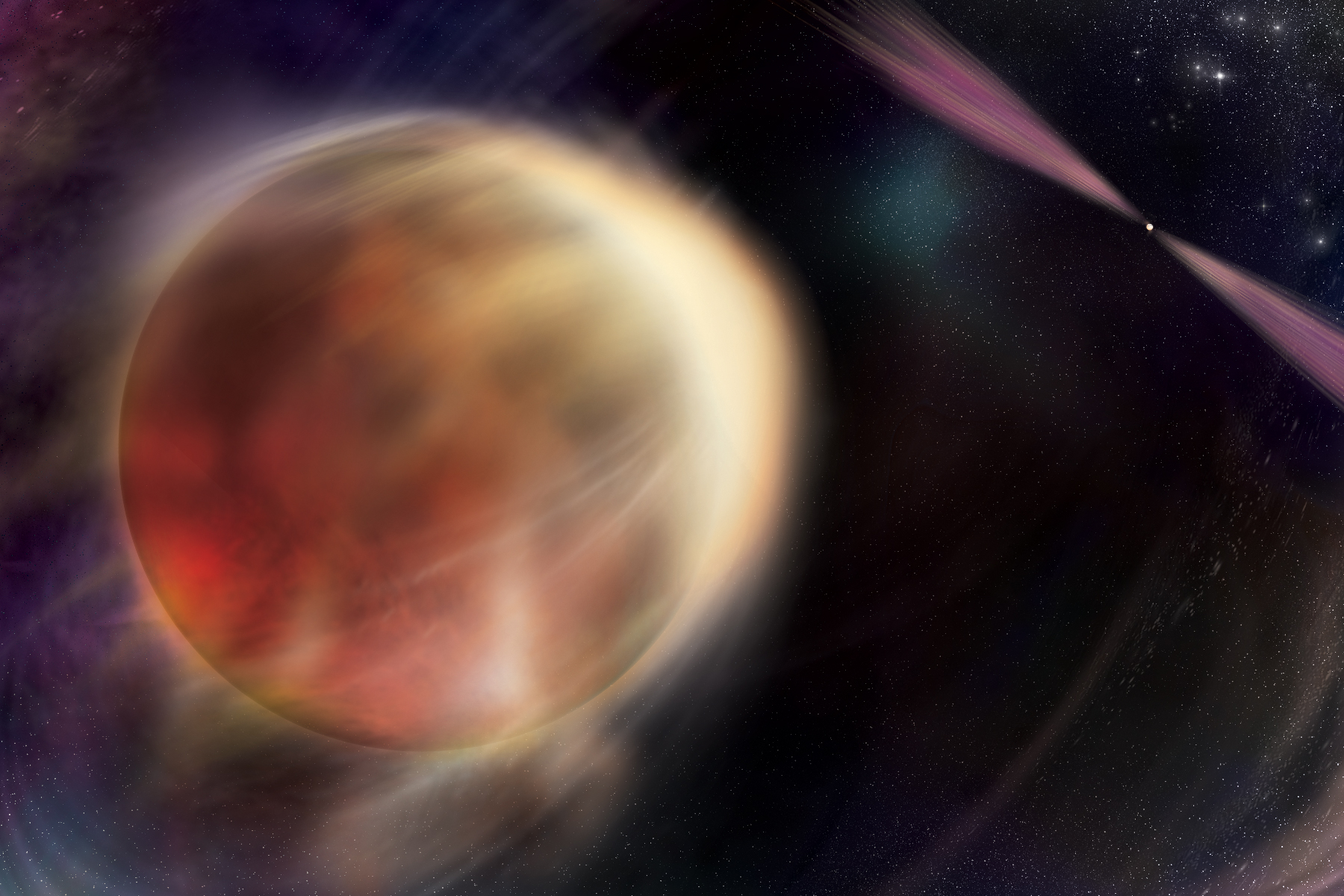

Fermi Spots Gamma-ray Eclipsing 'Spider Systems'

Go to this pageAn orbiting star begins to eclipse its partner, a rapidly rotating, superdense stellar remnant called a pulsar, in this illustration. The pulsar emits multiwavelength beams of light that rotate in and out of view and produces outflows that heat the star’s facing side, blowing away material and eroding its partner.Credit: NASA/Sonoma State University, Aurore Simonnet || GamRayEclipseG22.jpg (1800x1200) [1.1 MB] || GamRayEclipseG22_searchweb.png (320x180) [70.2 KB] || GamRayEclipseG22_thm.png (80x40) [6.8 KB] ||

2022

NASA’s Fermi, Swift Capture Revolutionary Gamma-Ray Burst

Go to this pageWatch to learn how an event called GRB 211211A rocked scientists’s understanding of gamma-ray bursts – the most powerful explosions in the cosmos.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic Credits: "Finished Plate" by Airglo and "Binary Fission" by Tom KaneWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel. || Title_Card_Revolutionary_GRB.jpg (1920x1080) [1.5 MB] || Title_Card_Revolutionary_GRB_searchweb.png (320x180) [100.7 KB] || Title_Card_Revolutionary_GRB_thm.png (80x40) [7.3 KB] || NASA’s_Fermi,_Swift_Capture_Revolutionary_Gamma-Ray_Burst.mp4 (1920x1080) [171.9 MB] || NASA’s_Fermi,_Swift_Capture_Revolutionary_Gamma-Ray_Burst_ProRes.mov (1920x1080) [2.2 GB] || NASA’s_Fermi,_Swift_Capture_Revolutionary_Gamma-Ray_Burst.webm (1920x1080) [18.4 MB] || Long_GRB_Captions.en_US.srt [2.8 KB] || Long_GRB_Captions.en_US.vtt [2.8 KB] ||

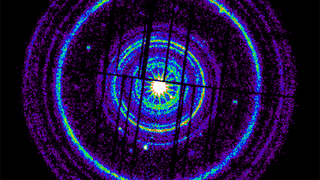

NASA Missions Detect Record-Breaking Burst

Go to this pageSwift’s X-Ray Telescope captured the afterglow of GRB 221009A about an hour after it was first detected. The bright rings form as a result of X-rays scattered by otherwise unobservable dust layers within our galaxy that lie in the direction of the burst. The dark vertical line is an artifact of the imaging system.Credit: NASA/Swift/A. Beardmore (University of Leicester) || XRT_image_crop.jpg (1084x1080) [629.3 KB] || XRT_image_crop_print.jpg (1024x1020) [657.0 KB] || XRT_image_crop_searchweb.png (320x180) [133.7 KB] || XRT_image_crop_web.png (320x318) [191.7 KB] || XRT_image_crop_thm.png (80x40) [26.1 KB] ||

NASA’s Fermi Confirms 'PeVatron' Supernova Remnant

Go to this pageExplore how astronomers located a supernova remnant that fires up protons to energies 10 times greater than the most powerful particle accelerator on Earth.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: New Philosopher by Laurent Dury; Universal Production MusicWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channelComplete transcript available. || 14170-Found__A_PeVatron.01978_print.jpg (1024x576) [61.1 KB] || 14170-PeVatron.mov (1920x1080) [1.8 GB] || 14170-_PeVatron.mp4 (1920x1080) [136.6 MB] || 14170-_PeVatron.webm (1920x1080) [15.1 MB] || 14170-PeVatron.en_US.vtt [2.3 KB] ||

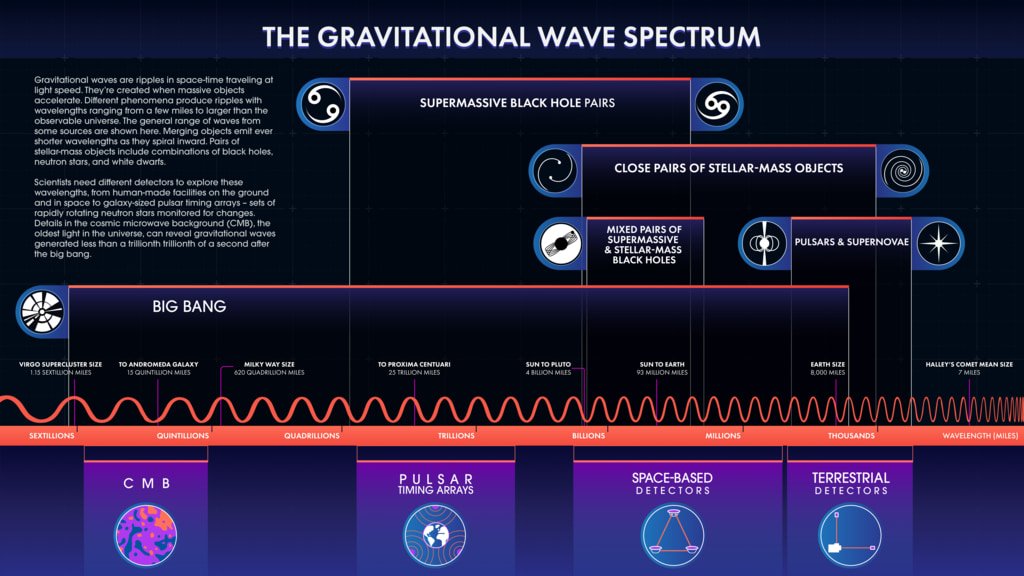

Fermi Searches for Gravitational Waves From Monster Black Holes

Go to this pageThe length of a gravitational wave, or ripple in space-time, depends on its source, as shown in this infographic. Scientists need different kinds of detectors to study as much of the spectrum as possible.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab || GravWav_Infographic_MILES_10k_vFinal_print.jpg (1024x576) [158.7 KB] || GravWav_Infographic_MILES_10k_vFinal.png (10000x5625) [2.1 MB] || GravWav_Infographic_MILES_10k_vFinal.jpg (10000x5625) [4.1 MB] || GravWav_Infographic_MILES_10k_vFinal_searchweb.png (320x180) [55.8 KB] || GravWav_Infographic_MILES_10k_vFinal_thm.png (80x40) [5.4 KB] ||

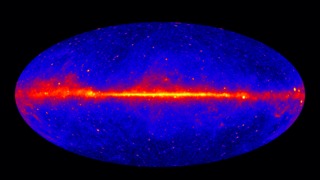

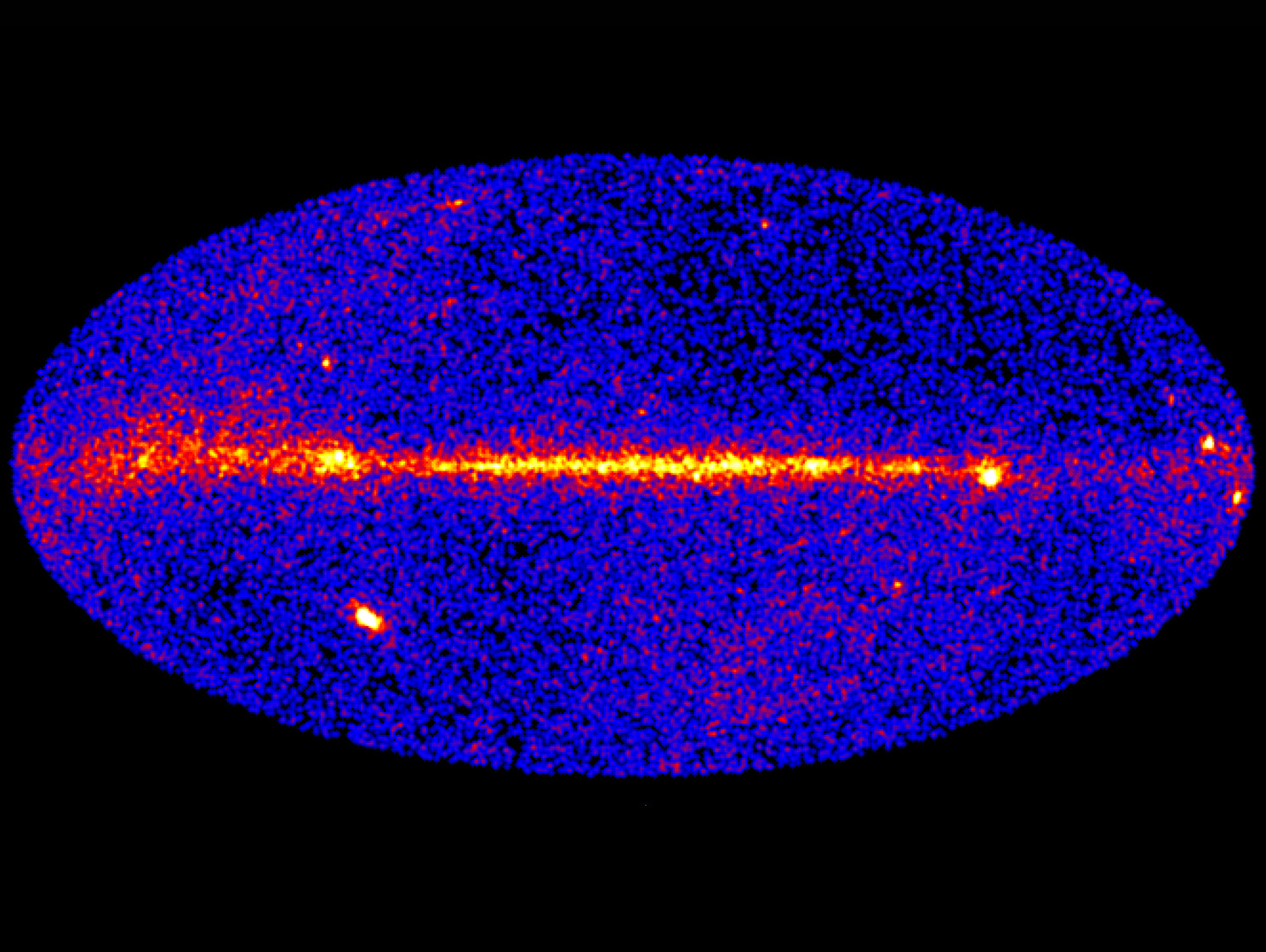

Fermi's 12-year View of the Gamma-ray Sky

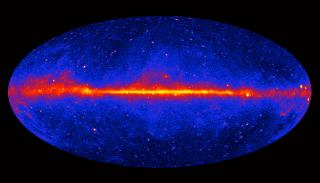

Go to this pageThis image shows the entire sky as seen by Fermi's Large Area Telescope. The most prominent feature is the bright, diffuse glow running along the middle of the map, which marks the central plane of our Milky Way galaxy. The gamma rays there are mostly produced when energetic particles accelerated in the shock waves of supernova remnants collide with gas atoms and even light between the stars. Many of the star-like features above and below the Milky Way plane are distant galaxies powered by supermassive black holes. Many of the bright sources along the plane are pulsars. The image was constructed from 12 years of observations using front-converting gamma rays with energies greater than 1 GeV. Hammer projection.Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration || Fermi_144-month_Fermi_all-sky_hammer_2160x1080.png (2160x1080) [2.4 MB] || Fermi_144-month_Fermi_all-sky_hammer_4000x2000.png (4000x2000) [7.0 MB] || Fermi_144-month_Fermi_all-sky_hammer_3600x1800.png (3600x1800) [4.9 MB] || Fermi_144-month_Fermi_all-sky_hammer_2160x1080_print.jpg (1024x512) [306.6 KB] ||

2021

NASA's Fermi Spots 'Fizzled' Burst from Collapsing Star

Go to this pageAstronomers combined data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, other space missions, and ground-based observatories to reveal the origin of GRB 200826A, a brief but powerful burst of radiation. It’s the shortest burst known to be powered by a collapsing star – and almost didn’t happen at all. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: "Inducing Waves" from Universal Production MusicWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || Fizzled_GRB_Still.jpg (1920x1080) [740.9 KB] || Fizzled_GRB_Still_print.jpg (1024x576) [286.8 KB] || Fizzled_GRB_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [72.2 KB] || Fizzled_GRB_Still_thm.png (80x40) [4.9 KB] || 13886_Fizzled_GRB_1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [147.2 MB] || 13886_Fizzled_GRB_1080_Best.mp4 (1920x1080) [453.2 MB] || 13886_Fizzled_GRB_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.5 GB] || 13886_Fizzled_GRB_1080.webm (1920x1080) [22.5 MB] ||

NASA Missions Unveil Magnetar Eruptions in Nearby Galaxies

Go to this pageOn April 15, 2020, a wave of X-rays and gamma rays lasting only a fraction of a second triggered detectors on NASA and European spacecraft. The event was a giant flare from a magnetar, a type of city-sized stellar remnant that boasts the strongest magnetic fields known. Watch to learn more.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: "Collision Course-Alternative Version" from Universal Production MusicWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || MGF_Video_Still.jpg (1920x1080) [602.3 KB] || MGF_Video_Still_print.jpg (1024x576) [264.7 KB] || MGF_Video_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [74.9 KB] || MGF_Video_Still_thm.png (80x40) [5.7 KB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.6 GB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_best_1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [498.6 MB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_good_1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [221.6 MB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_best_1080.webm (1920x1080) [24.0 MB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [4.0 KB] || 13792_Magnetar_Giant_Flare_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [4.0 KB] ||

2020

Young Active Galaxy with ‘TIE Fighter’ Shape

Go to this pageThis illustration shows two views of the active galaxy TXS 0128+554, located around 500 million light-years away. Left: The galaxy’s central jets appear as they would if we viewed them both at the same angle. The black hole, embedded in a disk of dust and gas, launches a pair of particle jets traveling at nearly the speed of light. Scientists think gamma rays (magenta) detected by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope originate from the base of these jets. As the jets collide with material surrounding the galaxy, they form identical lobes seen at radio wavelengths (orange). The jets experienced two distinct bouts of activity, which created the gap between the lobes and the black hole. Right: The galaxy appears in its actual orientation, with its jets tipped out of our line of sight by about 50 degrees.Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center || TXS0128_Side-by-Side_FInal.jpg (7680x2160) [1.8 MB] || TXS0128_Side-by-Side_FInal_Half.jpg (3840x1080) [601.5 KB] || TXS0128_Side-by-Side_FInal_print.jpg (1024x288) [45.4 KB] || TXS0128_Side-by-Side_FInal.jpg.dzi (7680x2160) [178 bytes] || TXS0128_Side-by-Side_FInal.jpg_files (1x1) [4.0 KB] ||

2019

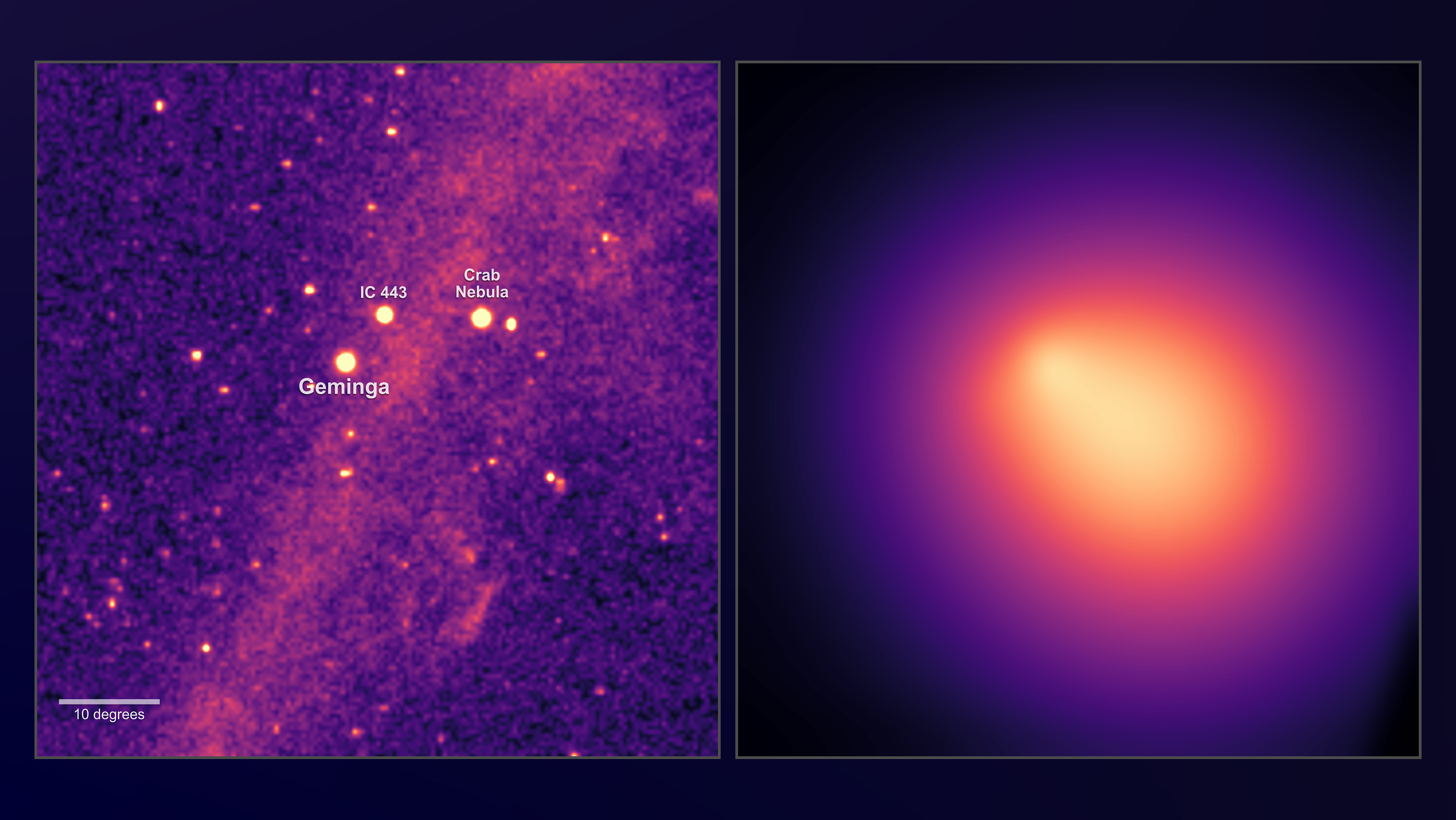

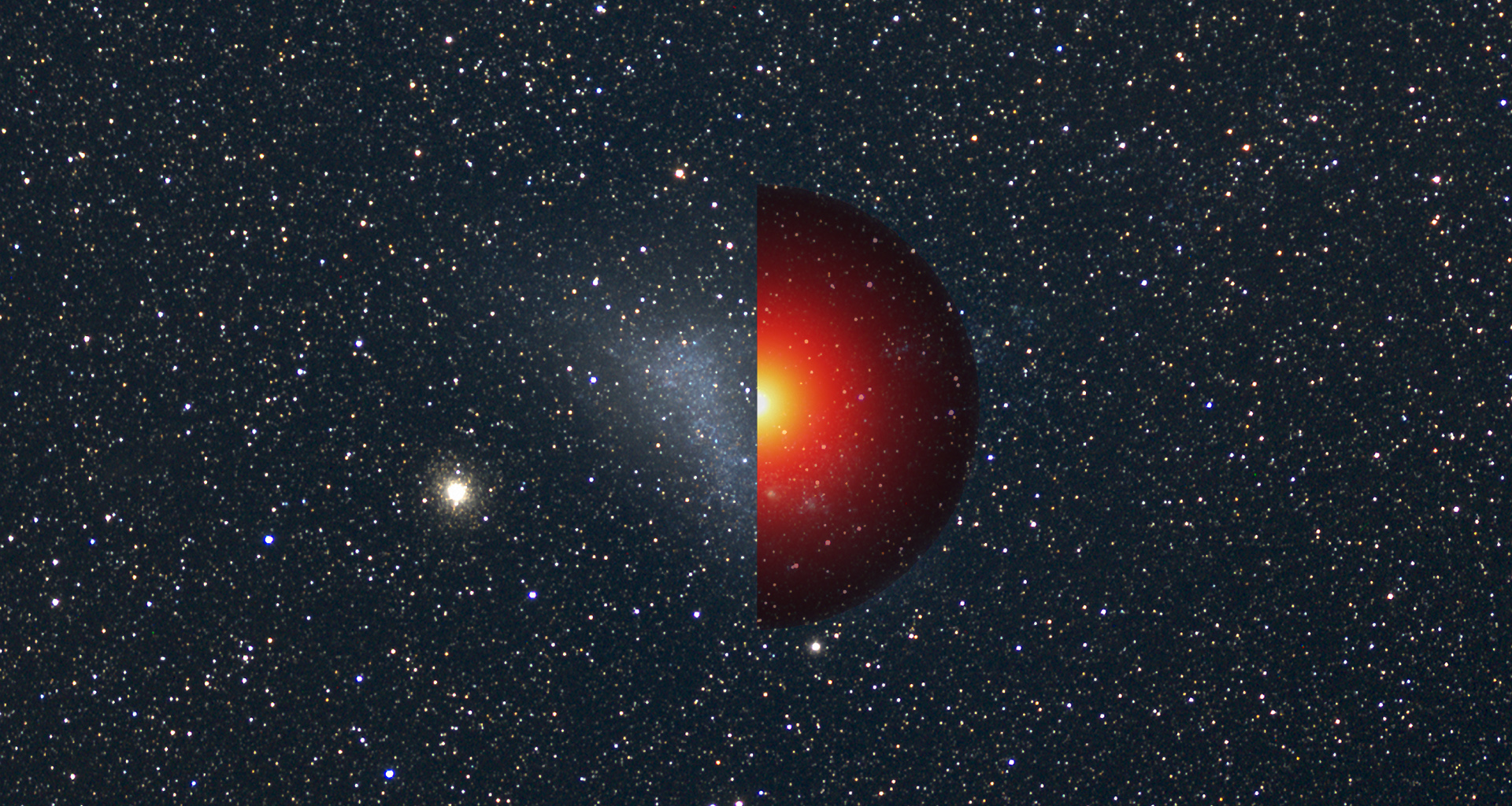

NASA’s Fermi Finds Vast ‘Halo’ Around Nearby Pulsar

Go to this sectionA new study of observations from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has discovered a faint but sprawling glow around a nearby pulsar. If visible to the human eye, this gamma-ray “halo” would appear larger in the sky than the famed Big Dipper star pattern. This structure may provide the solution to a long-standing mystery about the amount of antimatter in our neighborhood. Astronomers have been vexed by a decade-long puzzle about one type of cosmic particle arriving from beyond the solar system. Positrons, the antimatter version of electrons, turn out to unusually abundant near Earth. A neutron star is the crushed core left behind when a star much more massive than the Sun runs out of fuel, collapses under its own weight and explodes as a supernova. We see some neutron stars as pulsars, rapidly spinning objects emitting beams of radio waves, light, X-rays and gamma rays that, much like a lighthouse, regularly sweep across our line of sight. Geminga (pronounced geh-MING-ga) is among the brightest pulsars at gamma-ray energies.

To study its halo, scientists had to subtract out all other sources of gamma rays, including diffuse light produced by cosmic ray collisions with interstellar gas clouds. Ten different models of interstellar emission were evaluated. What remained when these sources were removed was a vast, oblong glow spanning some 20 degrees — about 40 times the apparent size of a full Moon — at an energy of 10 billion electron volts (GeV), and even larger at lower energies. The team determined that Geminga alone could be responsible for as much as 20% of the high-energy positrons seen by other space experiments. Extrapolating this to the cumulative emission of positrons from all pulsars in our galaxy, the scientists say it’s clear that pulsars remain the best explanation for the observed excess of positrons.A New Era in Gamma-ray Science

Go to this pageOn Jan. 14, 2019, the Major Atmospheric Gamma Imaging Cherenkov (MAGIC) observatory in the Canary Islands captured the highest-energy light every recorded from a gamma-ray burst. MAGIC began observing the fading burst just 50 seconds after it was detected thanks to positions provided by NASA's Fermi and Swift spacecraft (top left and right, respectively, in this illustration). The gamma rays packed energy up to 10 times greater than previously seen. Credit: NASA/Fermi and Aurore Simonnet, Sonoma State University || GRB190114CbASimonnet.jpg (2475x3300) [4.5 MB] || GRB190114CbASimonnet_searchweb.png (320x180) [106.4 KB] || GRB190114CbASimonnet_thm.png (80x40) [6.6 KB] ||

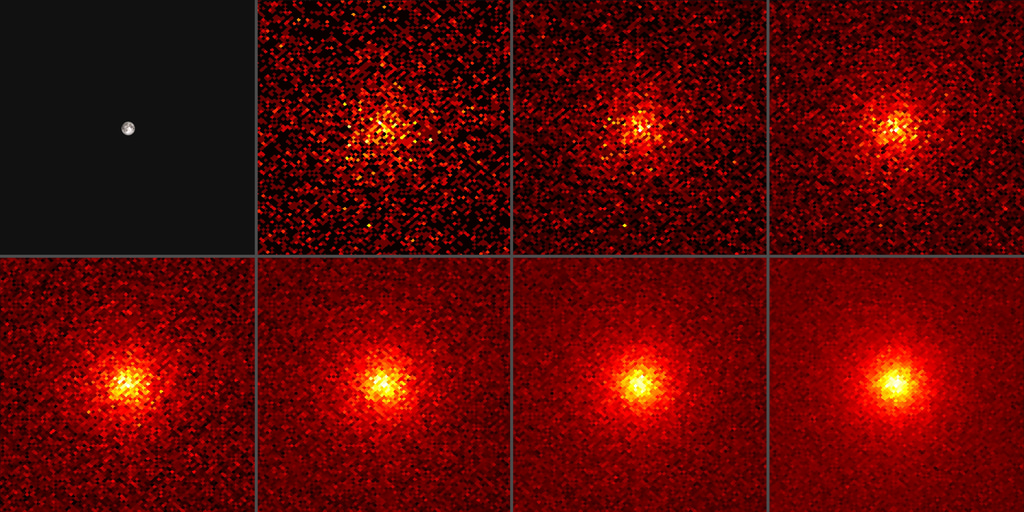

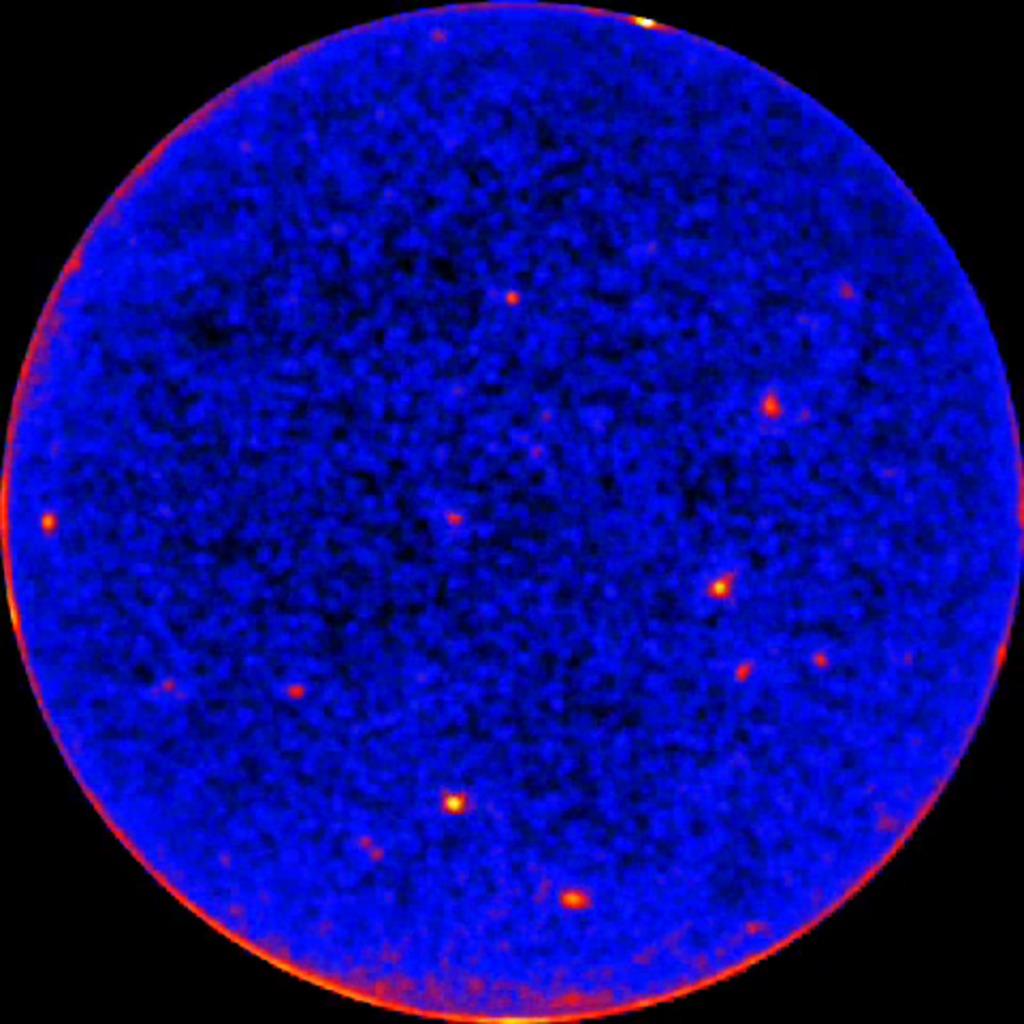

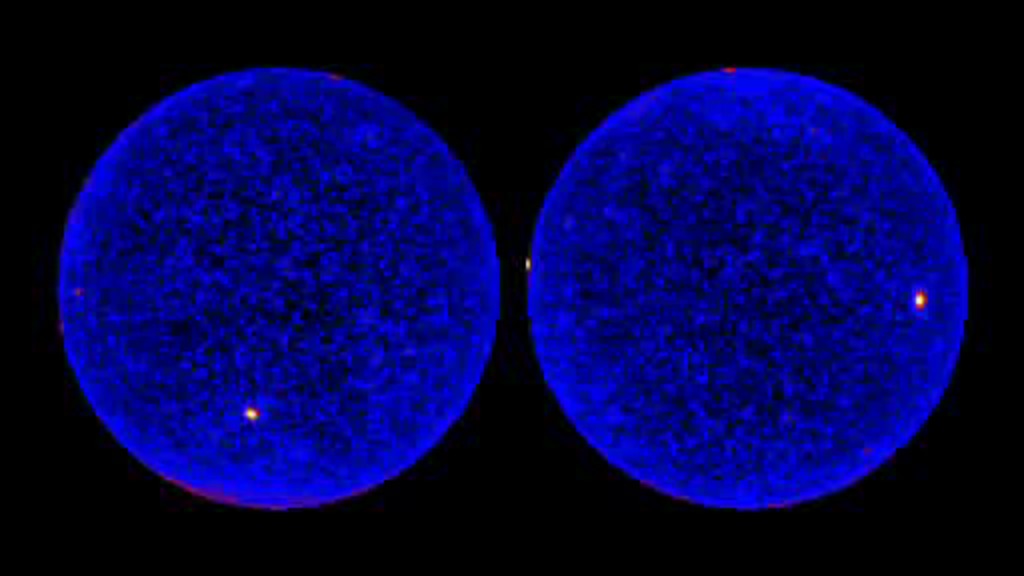

Fermi Sees the Moon in Gamma Rays

Go to this pageThese images show the steadily improving view of the Moon’s gamma-ray glow from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Each 5-by-5-degree image is centered on the Moon and shows gamma rays with energies above 31 million electron volts, or tens of millions of times that of visible light. At these energies, the Moon is actually brighter than the Sun. Brighter colors indicate greater numbers of gamma rays. This image sequence shows how longer exposure, ranging from two to 128 months (10.7 years), improved the view.Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration || MoonvsTimesingleimageen.jpg (4322x2161) [5.2 MB] ||

Ten Years of High-Energy Gamma-ray Bursts

Go to this pageGreen dots show the locations of 186 gamma-ray bursts observed by the Large Area Telescope (LAT) on NASA’s Fermi satellite during its first decade. Some noteworthy bursts are highlighted and labeled. Background: Constructed from nine years of LAT data, this map shows how the gamma-ray sky appears at energies above 10 billion electron volts. The plane of our Milky Way galaxy runs along the middle of the plot. Brighter colors indicate brighter gamma-ray sources.Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration || Fermi_LAT_GRBs.jpg (5991x2994) [2.1 MB] ||

NASA’s Fermi Satellite Clocks a ‘Cannonball’ Pulsar

Go to this pageNew radio observations combined with 10 years of data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have revealed a runaway pulsar that escaped the blast wave of the supernova that formed it. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: "Forensic Scientist" from Killer TracksWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available.See the bottom of the page for a version without on-screen text. || CTA1_Still.jpg (1920x1080) [291.7 KB] || CTA1_Still_print.jpg (1024x576) [137.4 KB] || CTA1_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [86.6 KB] || CTA1_Still_thm.png (80x40) [7.2 KB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.0 GB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_Best.mov (1920x1080) [727.8 MB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_Good.mp4 (1920x1080) [400.9 MB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar.mp4 (1920x1080) [147.3 MB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar.m4v (1920x1080) [144.6 MB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.webm (1920x1080) [15.7 MB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [1.9 KB] || 13156_CTB1_Cannonball_Pulsar_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [1.9 KB] ||

2018

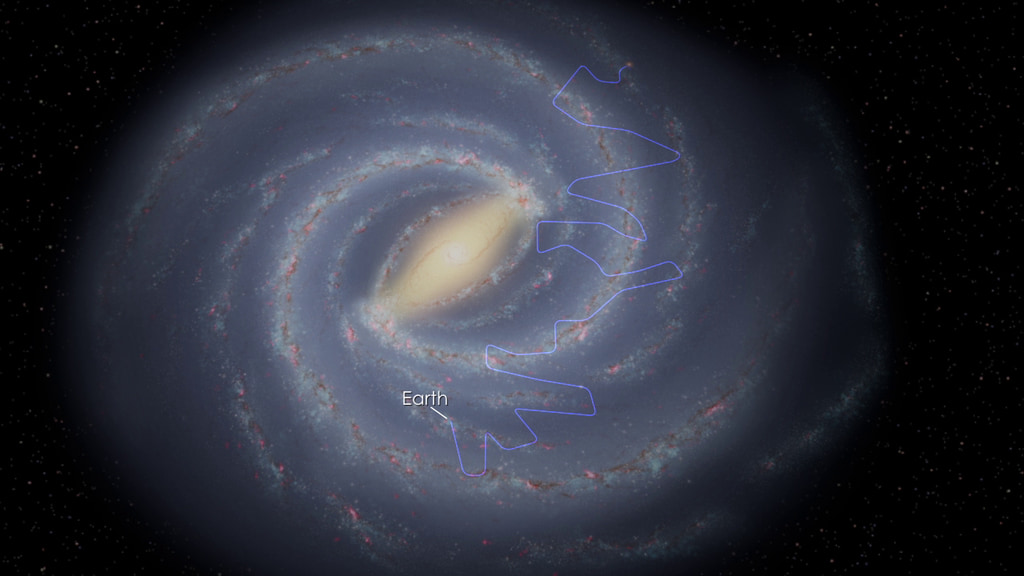

Tracing the History of Starlight with NASA's Fermi Mission

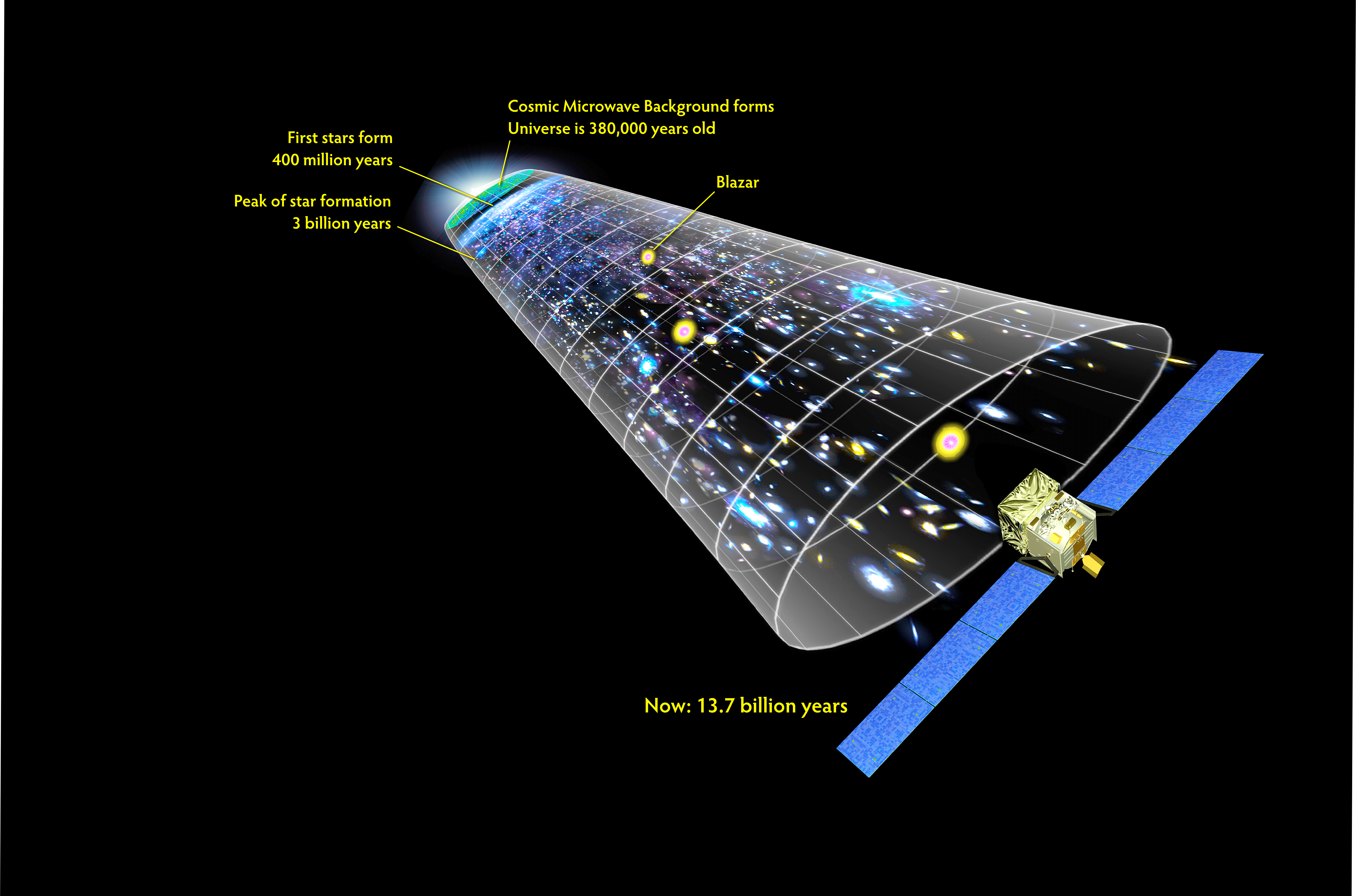

Go to this sectionScientists using data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have measured all the starlight produced over 90 percent of the universe’s history. The analysis, which examines the gamma-ray output of distant galaxies, estimates the formation rate of stars and provides a reference for future missions that will explore the still-murky early days of stellar evolution. One of the main goals of the Fermi mission is to assess the extragalactic background light (EBL), a cosmic fog composed of all the ultraviolet, visible and infrared light stars have created over the universe’s history. Because starlight continues to travel across the cosmos long after its sources have burned out, measuring the EBL allows astronomers to study stellar formation and evolution separately from the stars themselves. The collision between a high-energy gamma ray and infrared light transforms the energy into a pair of particles, an electron and its antimatter counterpart, a positron. The same process occurs when medium-energy gamma rays interact with visible light, and low-energy gamma rays interact with ultraviolet light. Enough of these interactions occur over cosmic distances that the farther back scientists look, the more evident their effects become on gamma-ray sources, enabling a deep probe of the universe’s stellar content. The scientists examined gamma-ray signals from 739 blazars — galaxies with monster black holes at their centers — collected over nine years by Fermi’s Large Area Telescope (LAT). The measurement quintuples the number of blazars used in an earlier Fermi EBL analysis published in 2012 and includes new calculations of how the EBL builds over time, revealing the peak of star formation around 10 billion years ago.

NASA's Fermi Mission Shows How Luck Favors the Prepared

Go to this sectionIn 2017, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope played a pivotal role in two important breakthroughs occurring just five weeks apart. But what might seem like extraordinary good luck is really the product of research, analysis, preparation and development extending back more than a century. This video timeline explores the historical progress of research into three cosmic messengers -- gravitational waves, gamma rays and neutrinos -- that Fermi helped bring together. For some of the video content used in this timeline, see this page.

Fermi Scientists Introduce Gamma-ray Constellations

Go to this pageScientists with NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope devised a set of constellations for the high-energy sky to highlight the mission’s 10th year of operations. Characters from modern myths, like the Hulk and the time-warping TARDIS from “Doctor Who,” represent one source of inspiration. Others include scientific concepts and tools, like the Fermi Satellite, and famous landmarks in countries contributing to the development and operation of Fermi. The mission has mapped about 3,000 gamma-ray sources -- 10 times the number known before its launch and comparable to the number of bright stars in the traditional constellations. The background shows the gamma-ray sky as mapped by Fermi. The prominent reddish band is the plane of our own galaxy, the Milky Way; brighter colors indicate brighter gamma-ray sources. Credit: NASA || GR_Constellations-NorthFermi_FullSize_FInal.gif (1920x930) [4.4 MB] ||

Simulations Create New Insights Into Pulsars

Go to this sectionScientists studying what amounts to a computer-simulated “pulsar in a box” are gaining a more detailed understanding of the complex, high-energy environment around spinning neutron stars, also called pulsars. The model traces the paths of charged particles in magnetic and electric fields near the neutron star, revealing behaviors that may help explain how pulsars emit gamma-ray and radio pulses with ultraprecise timing. A pulsar is the crushed core of a massive star that exploded as a supernova. The core is so compressed that more mass than the Sun's squeezes into a ball no wider than Manhattan Island in New York City. This process also revs up its rotation and strengthens its magnetic and electric fields. Various physical processes ensure that most of the particles around a pulsar are either electrons or their antimatter counterparts, positrons. To trace the behavior and energies of these particles, the researchers used a comparatively new type of pulsar model called a “particle in cell” (PIC) simulation. The PIC technique lets scientists explore the pulsar from first principles, starting with a spinning, magnetized neutron star. The computer code injects electrons and positrons at the pulsar's surface and tracks how they interact with the electric and magnetic fields. It's computationally intensive because the particle motions affect the fields and the fields affect the particles, and everything is moving near the speed of light. The simulation shows that most of the electrons tend to race outward from the magnetic poles. Some medium-energy electrons scatter wildly, even heading back to the pulsar. The positrons, on the other hand, mostly flow out at lower latitudes, forming a relatively thin structure called the current sheet. In fact, the highest-energy positrons here — less than 0.1 percent of the total — are capable of producing gamma rays similar to those detected by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which has discovered 216 gamma-ray pulsars. The simulation ran on the Discover supercomputer at NASA’s Center for Climate Simulation at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the Pleiades supercomputer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California. The model actually tracks “macroparticles,” each of which represents many trillions of electrons or positrons.

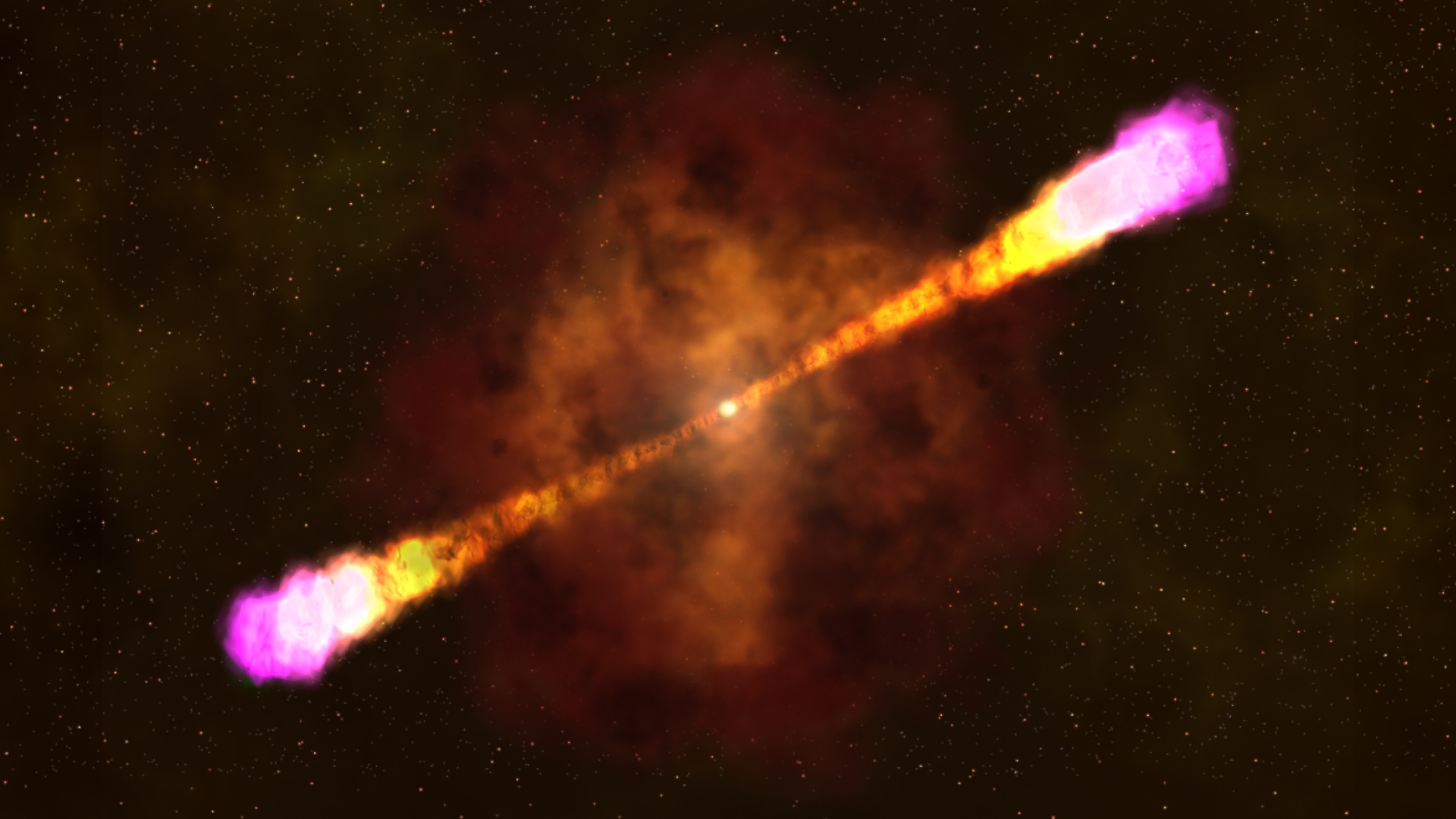

NASA's Fermi Links Cosmic Neutrino to Monster Black Hole

Go to this sectionFor the first time ever, scientists using NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have found the source of a high-energy neutrino from outside our galaxy. This neutrino travelled 3.7 billion years at nearly light speed before being detected on Earth -- farther than any other neutrino we know the origin of. High-energy neutrinos are hard-to-catch particles that scientists think are created by the most powerful events in the cosmos, like galaxy mergers and material falling onto supermassive black holes. They travel a whisker shy of the speed of light and rarely interact with other matter, so they can travel unimpeded across billions of light-years. On Sept. 22, 2017, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole detected signs of a neutrino striking the Antarctic ice with an energy of about 300 trillion electron volts -- more than 45 times the energy achievable in the most powerful particle accelerator on Earth. This high energy strongly suggested that the neutrino had to be from beyond our solar system. Backtracking the path through IceCube indicated where in the sky the neutrino came from, and automated alerts notified astronomers around the globe to search this region for flares or outbursts that could be associated with the event. Data from Fermi’s Large Area Telescope revealed enhanced gamma-ray emission from a well-known active galaxy at the time the neutrino arrived. This active galaxy is a type called a blazar, where a supermassive black hole with millions to billions of times the Sun’s mass that blasts particle jets outward in opposite directions at nearly the speed of light. Blazars are especially bright and active because one of these jets happens to point almost directly toward Earth. Fermi showed that at the time of the neutrino detection, the blazar TXS 0506+056 was the most active it had been in a decade. The discovery is a giant leap forward in a growing field called multimessenger astronomy, where new cosmic signals like neutrinos and gravitational waves are definitively linked to sources that emit light.

Fermi Satellite Celebrates 10 Years of Discoveries

Go to this pageWatch a two-minute video on how NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has revolutionized our understanding of the high-energy sky over its first 10 years in space. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight CenterMusic: "Unseen Husband" from Killer TracksWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || Fermi_10_Still.jpg (1920x1080) [134.3 KB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.3 GB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_1080.m4v (1920x1080) [172.3 MB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_1080p.mov (1920x1080) [259.5 MB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short.mp4 (1920x1080) [174.7 MB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.webm (1920x1080) [18.7 MB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [3.3 KB] || 12969_Fermi_10th_Short_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [3.3 KB] ||

2017

Doomed Neutron Stars Create Blast of Light and Gravitational Waves

Go to this pageThis animation captures phenomena observed over the course of nine days following the neutron star merger known as GW170817, detected on Aug. 17, 2017. They include gravitational waves (pale arcs), a near-light-speed jet that produced gamma rays (magenta), expanding debris from a kilonova that produced ultraviolet (violet), optical and infrared (blue-white to red) emission, and, once the jet directed toward us expanded into our view from Earth, X-rays (blue). Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/CI LabMusic: "Exploding Skies" from Killer TracksWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new_1080.png (1920x1080) [2.5 MB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new_1080.jpg (1920x1080) [167.3 KB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new_print.jpg (1024x576) [50.4 KB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new.png (3840x2160) [7.7 MB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new.jpg (3840x2160) [1.0 MB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new_searchweb.png (320x180) [51.4 KB] || Neutron_Star_Merger_Still_2_new_thm.png (80x40) [4.4 KB] || 12740_NS_Merger_Update_1080.m4v (1920x1080) [50.3 MB] || 12740_NS_Merger_Update_H264_1080.mp4 (1920x1080) [96.9 MB] || 12740_NS_Merger_Update_1080p.mov (1920x1080) [101.9 MB] || NS_Merger_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [417 bytes] || NS_Merger_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [399 bytes] || 12740_NS_Merger_4k_Update.webm (3840x2160) [10.0 MB] || 12740_NS_Merger_4k_Update_H264.mp4 (3840x2160) [254.9 MB] || 12740_NS_Merger_4k_Update_H264.mov (3840x2160) [516.7 MB] || 12740_NS_Merger_4k_Update_ProRes_3840x2160_5994.mov (3840x2160) [5.1 GB] ||

Fermi Detects Gamma-ray Puzzle from M31

Go to this pageNASA's Fermi telescope has detected a gamma-ray excess at the center of the Andromeda Galaxy that's similar to a signature Fermi previously detected at the center of our own Milky Way. Watch to learn more. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Scott Wiessinger, producerMusic: "Lost Time" from Killer TracksWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.Complete transcript available. || 12505_Fermi_M31_FINAL_appletv.00382_print.jpg (1024x576) [172.8 KB] || Fermi_M31_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [92.6 KB] || Fermi_M31_Still_thm.png (80x40) [5.9 KB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [1.1 GB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_FINAL_youtube_hq.mov (1920x1080) [674.5 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_1080p.mov (1920x1080) [128.2 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_Good_1080.m4v (1920x1080) [85.0 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_FINAL_appletv.m4v (1280x720) [41.7 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_Compatible.m4v (960x540) [34.7 MB] || WMV_12505_Fermi_M31_FINAL_HD.wmv (1920x1080) [205.4 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_FINAL_appletv_subtitles.m4v (1280x720) [41.7 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_Compatible.webm (960x540) [9.0 MB] || 12505_Fermi_M31_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [854 bytes] || 12505_Fermi_M31_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [867 bytes] ||

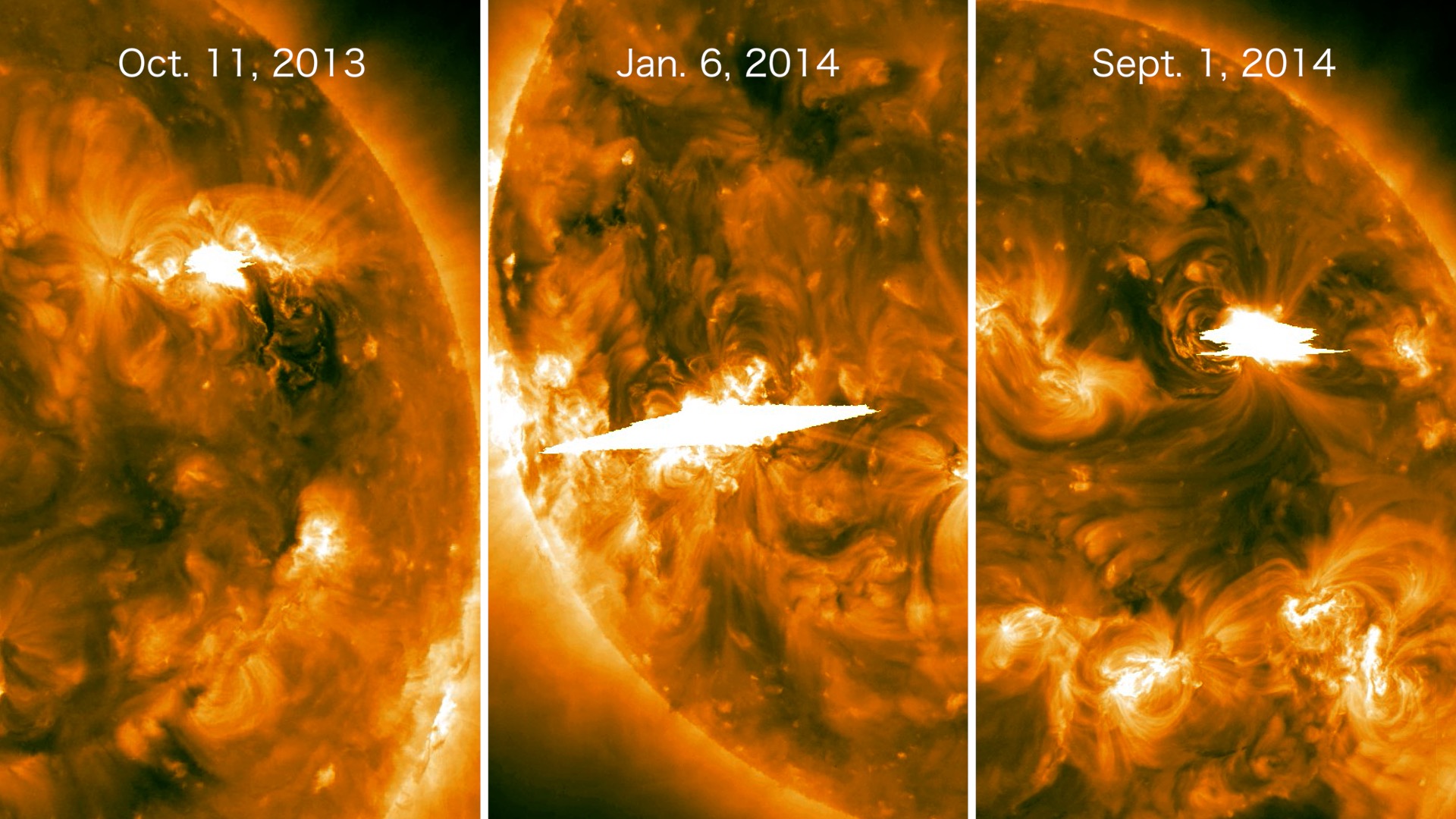

Fermi Sees Gamma Rays from Far Side Solar Flares

Go to this sectionAn international science team says NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has observed high-energy light from solar eruptions located on the far side of the sun, which should block direct light from these events. This apparent paradox is providing solar scientists with a unique tool for exploring how charged particles are accelerated to nearly the speed of light and move across the sun during solar flares. Fermi has seen gamma rays from the Earth-facing side of the sun, but the emission is produced by streams of particles blasted out of solar flares on the far side These particles must travel some 300,000 miles within about five minutes of the eruption to produce this light. Fermi has doubled the number of these rare events, called behind-the-limb flares, since it began scanning the sky in 2008. Its Large Area Telescope (LAT) has captured gamma rays with energies reaching 3 billion electron volts, some 30 times greater than the most energetic light previously associated with these "hidden" flares. Thanks to NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft, which were monitoring the solar far side when the eruptions occurred, the Fermi events mark the first time scientists have direct imaging of beyond-the-limb solar flares associated with high-energy gamma rays. The hidden flares occurred Oct. 11, 2013, and Jan. 6 and Sept. 1, 2014. All three events were associated with fast coronal mass ejections (CMEs), where billion-ton clouds of solar plasma were launched into space. The CME from the most recent event was moving at nearly 5 million miles an hour as it left the sun. Researchers suspect particles accelerated at the leading edge of the CMEs were responsible for the gamma-ray emission. Large magnetic field structures can connect the acceleration site with distant part of the solar surface. Because charged particles must remain attached to magnetic field lines, the research team thinks particles accelerated at the CME traveled to the sun's visible side along magnetic field lines connecting both locations. As the particles impacted the surface, they generated gamma-ray emission through a variety of processes. One prominent mechanism is thought to be proton collisions that result in a particle called a pion, which quickly decays into gamma rays.

2016

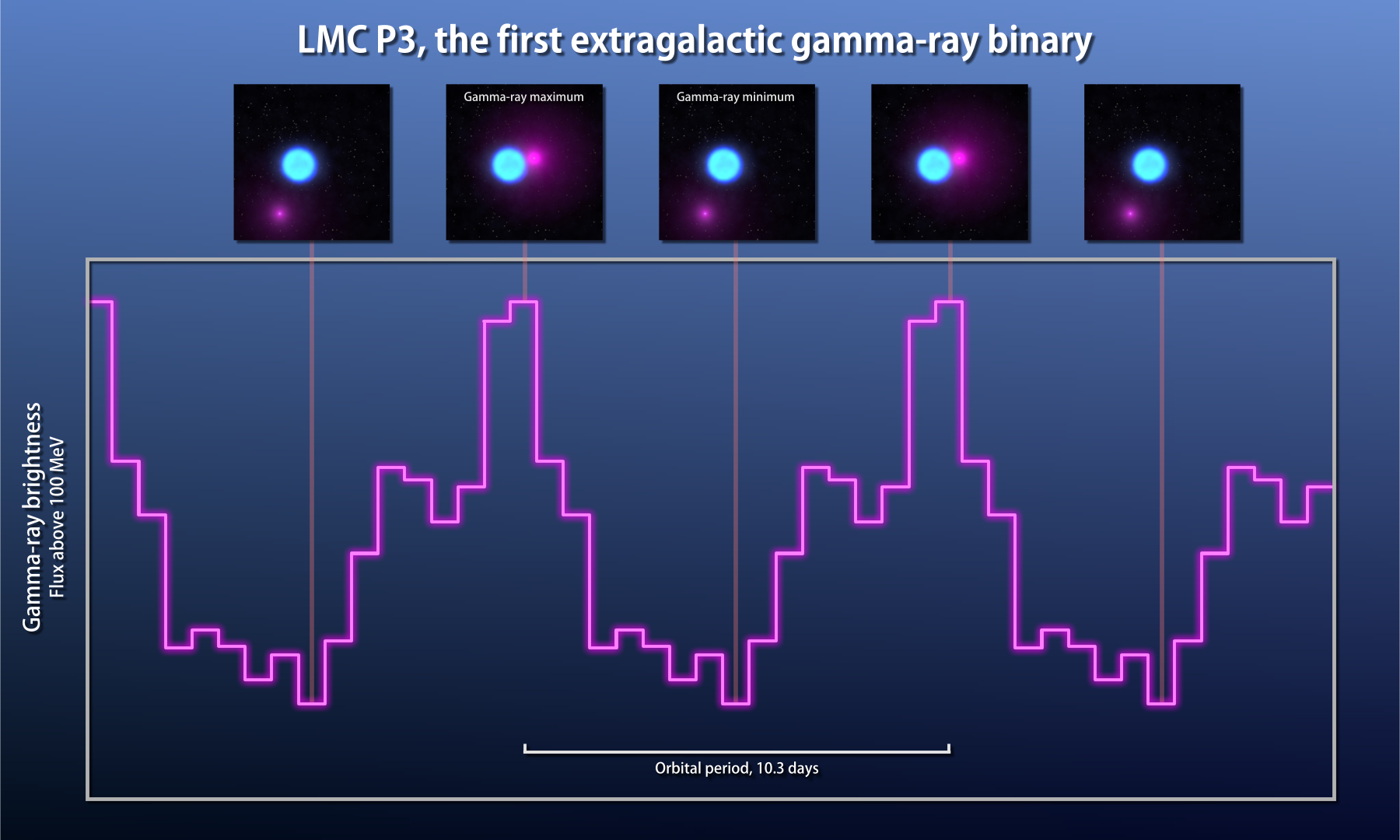

Fermi Finds Record-breaking Gamma-ray Binary

Go to this sectionUsing data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and other facilities, scientists have found the first gamma-ray binary in another galaxy and the most luminous one ever seen. The dual-star system, dubbed LMC P3, contains a massive star and a crushed stellar core that interact to produce a cyclic flood of gamma rays, the highest-energy form of light. Gamma-ray binaries are rare -- only six are known in our own galaxy, and one remains undetected by Fermi. The systems are prized because their gamma-ray output changes significantly during each orbit and sometimes over longer time scales. This variation lets astronomers study many of the emission processes common to other gamma-ray sources in unique detail. The systems contain either a neutron star or a black hole and radiate most of their energy in the form of gamma rays. Remarkably, LMC P3 is the most luminous such system known in gamma rays, X-rays, radio waves and visible light, and it's only the second one discovered with Fermi. LMC P3 lies within a supernova remnant located in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a small nearby galaxy about 163,000 light-years away. In 2012, scientists using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory found a strong X-ray source within the remnant and showed that it was orbiting a hot, young star many times the sun's mass. The researchers concluded the compact object was either a neutron star or a black hole and classified the system as a high-mass X-ray binary (HMXB). In 2015, a team led by Robin Corbet at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center began looking for new gamma-ray binaries in Fermi data by searching for the periodic changes characteristic of these systems. The scientists discovered a 10.3-day cyclic change centered near one of several gamma-ray point sources recently identified in the LMC. One of them, called P3, was not linked to objects seen at any other wavelengths but was located near the HMXB. Were they the same object? Observations from NASA's Swift satellite clearly reveal the same 10.3-day cycle seen in gamma rays by Fermi. They also indicate that the brightest X-ray emission occurs opposite the gamma-ray peak, so when one reaches maximum the other is at minimum. Radio data exhibit the same period and out-of-phase relationship with the gamma-ray peak, confirming that LMC P3 is indeed the same system investigated by Chandra. Prior to Fermi's launch, gamma-ray binaries were expected to be more numerous than they've turned out to be. It's a puzzle because hundreds of HMXBs are cataloged, and all of them are thought to have originated as gamma-ray binaries following the supernova that formed the compact object. Its possible gamma-ray binaries may form only from neutron stars born with the fastest spins, which would enhance their ability to produce gamma rays.

NASA's Fermi Mission Broadens its Dark Matter Search

Go to this pageTop: Gamma rays (magenta lines) coming from a bright source like NGC 1275 in the Perseus galaxy cluster should form a particular type of spectrum (right). Bottom: Gamma rays convert into hypothetical axion-like particles (green dashes) and back again when they encounter magnetic fields (gray curves). The resulting gamma-ray spectrum (lower curve at right) would show unusual steps and gaps not seen in Fermi data, which means a range of these particles cannot make up a portion of dark matter.Credit: SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory/Chris Smith || ALP_2_sequences.gif (1074x580) [211.8 KB] ||

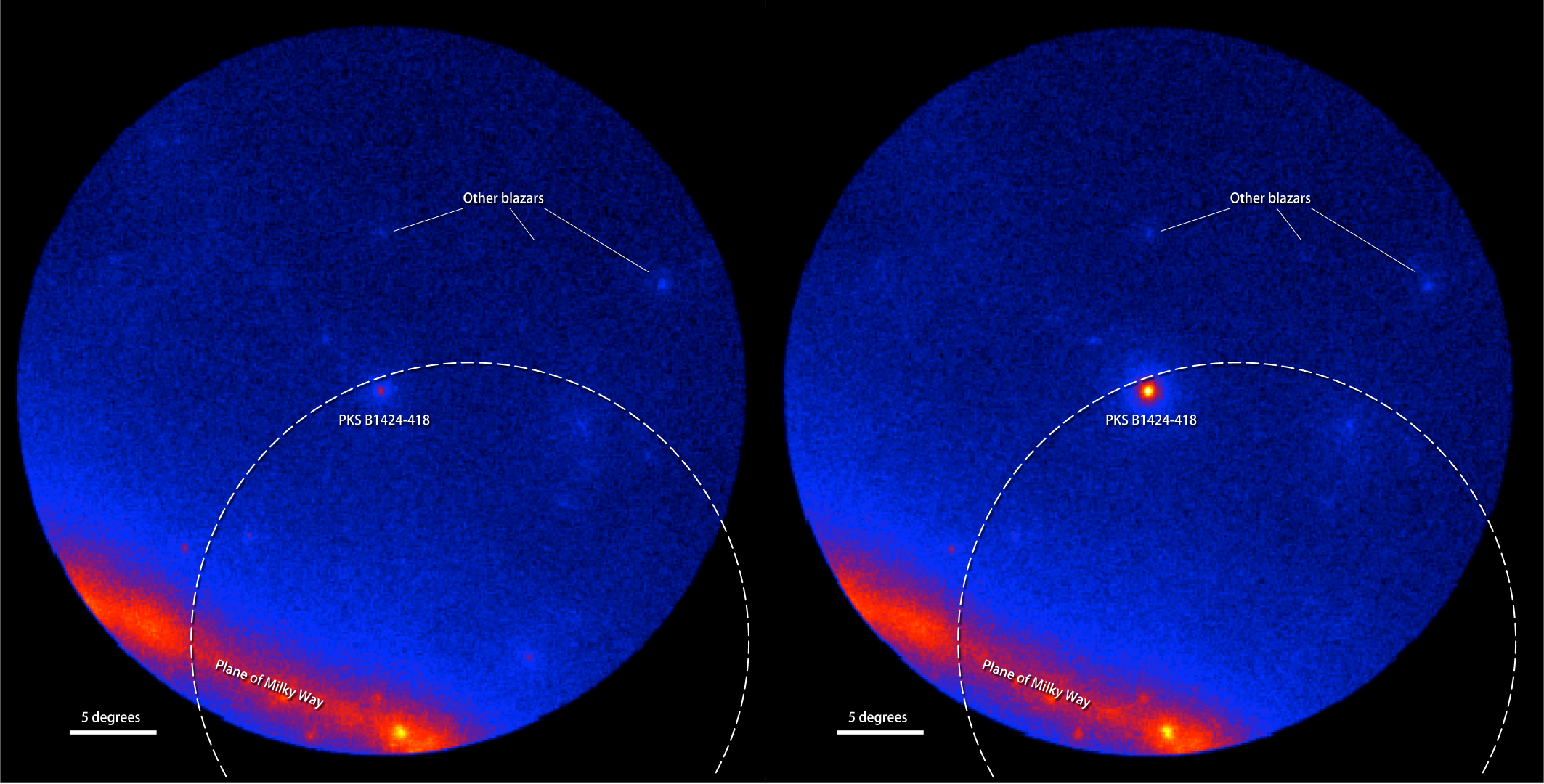

Fermi Helps Link a Cosmic Neutrino to a Blazar Outburst

Go to this sectionNearly 10 billion years ago, the black hole at the center of a distant galaxy produced a powerful outburst, and light from this blast began arriving at Earth in 2012. Astronomers using data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and other space- and ground-based observatories have shown that a record-breaking neutrino seen around the same time likely was born in the same event. Neutrinos are the fastest, lightest, most unsociable and least understood fundamental particles. The study provides the first plausible association between a single extragalactic object and a high-energy cosmic neutrino. Although neutrinos far outnumber all the atoms in the universe, they rarely interact with matter. While this property makes them hard to detect, it lets neutrinos make a fast exit from places where light cannot easily escape -- such as the core of a collapsing star -- and zip across the universe almost completely unimpeded. Neutrinos can provide information about processes and environments that simply aren't available through a study of light alone. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory, built into a cubic kilometer of clear glacial ice at the South Pole, detects neutrinos when they interact with atoms in the ice. Some of the most extreme particles detected by IceCube receive nicknames based on characters on the children's TV series "Sesame Street." On Dec. 4, 2012, IceCube detected an event known as Big Bird, a neutrino with an energy exceeding 2 quadrillion electron volts (PeV), the highest-energy neutrino ever detected at the time. But the best IceCube position only narrowed the source to a patch of the southern sky about 32 degrees across, equivalent to the apparent size of 64 full moons. In the summer of 2012, Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) witnessed the onset of a dramatic brightening of PKS B1424-418, an active galaxy classified as a gamma-ray blazar. An active galaxy is an otherwise typical galaxy with a compact and unusually bright core; this excess luminosity is produced by matter falling toward a supermassive black hole weighing millions of times the mass of our sun. As it approaches the black hole, some of the material becomes channeled into particle jets moving outward in opposite directions at nearly the speed of light. In blazars, one of these jets happens to point almost directly toward Earth. During the year-long outburst, PKS B1424-418 shone between 15 and 30 times brighter in gamma rays than its average before the eruption. The blazar is located within the Big Bird source region, but so are many other active galaxies detected by Fermi. Was it the culprit? Astronomers investigating the link turned to the TANAMI project, which since 2007 has routinely monitored dozens of active galaxies in the southern sky. The program includes regular radio observations using the Australian Long Baseline Array (LBA) and associated telescopes in Chile, South Africa, New Zealand and Antarctica. When networked together, they operate as a single radio telescope more than 6,000 miles across and provide a unique high-resolution look into the jets of active galaxies. Three radio observations of PKS B1424-418 between 2011 and 2013 cover the period of the Fermi outburst. They reveal that the core of the galaxy's jet had brightened by about four times. No other galaxy observed by TANAMI over the life of the program has exhibited such a dramatic change. The team suggests the PKS B1424-418 outburst and Big Bird are connected, calculating only a 5-percent probability the two events occurred by chance alone. Using data from Fermi, NASA’s Swift and WISE satellites, the LBA and other facilities, the researchers determined how the energy of the eruption was distributed across the electromagnetic spectrum and showed that it was sufficiently powerful to produce a neutrino at PeV energies.

NASA's Fermi Preps to Narrow Down Gravitational Wave Sources

Go to this pageFermi's GBM saw a fading X-ray flash at nearly the same moment LIGO detected gravitational waves from a black hole merger in 2015. This movie shows how scientists can narrow down the location of the LIGO source on the assumption that the burst is connected to it. In this case, the LIGO search area is reduced by two-thirds. Greater improvements are possible in future detections.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Watch this video on the NASAgovVideo YouTube channel. || LIGO_GBM_Common_only_Earth.png (1920x1080) [4.2 MB] || LIGO_GBM_Common_only_Earth_print.jpg (1024x576) [168.3 KB] || LIGO_GBM_Common_only_Earth_searchweb.png (320x180) [97.0 KB] || LIGO_GBM_Common_only_Earth_web.png (320x180) [97.0 KB] || LIGO_GBM_Common_only_Earth_thm.png (80x40) [6.6 KB] || Fermi_LIGO_GBM_localizations_H264_YouTube_1080p.mp4 (1920x1080) [82.8 MB] || Fermi_LIGO_GBM_localizations_H264_720p.mp4 (1280x720) [35.4 MB] || Fermi_LIGO_GBM_localizations_H264_720p.webm (1280x720) [2.3 MB] || Fermi_LIGO_GBM_localizations_ProRes_1920x1080_30.mov (1920x1080) [431.3 MB] || 12216_Fermi_LIGO_Localization_4K.mov (4096x2304) [90.6 MB] || 12216_Fermi_LIGO_Localization_4K.m4v (3840x2160) [140.3 MB] || 12216_Fermi_LIGO_Localization_ProRes_7282x4096_30.mov (7282x4096) [6.0 GB] ||

NASA's Fermi Mission Sharpens its High-energy View

Go to this pageTour the best view of the high-energy gamma-ray sky yet seen. This video highlights the plane of our galaxy and identifies objects producing gamma rays with energies greater than 1 TeV. Watch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.For complete transcript, click here.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center || 2FHL_Still_print.jpg (1024x576) [66.4 KB] || 2FHL_Still.png (3840x2160) [19.0 MB] || 2FHL_Still_searchweb.png (320x180) [55.9 KB] || 2FHL_Still_thm.png (80x40) [5.5 KB] || 12019_2FHL_H264_Good_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [39.6 MB] || 12019_2FHL_H264_Good_1920x1080_2997.webm (1920x1080) [9.9 MB] || 12019_2FHL_3840x2160_FINAL_appletv.m4v (1280x720) [49.2 MB] || 12019_2FHL_3840x2160_FINAL_appletv_subtitles.m4v (1280x720) [49.3 MB] || 12019_2FHL_3840x2160_FINAL_lowres.mp4 (480x272) [13.0 MB] || NASA_PODCAST_12019_2FHL_3840x2160_FINAL_ipod_sm.mp4 (320x240) [17.8 MB] || 12019_2FHL_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [330 bytes] || 12019_2FHL_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [343 bytes] || 12019_2FHL_ProRes_3840x2160_2997.mov (3840x2160) [3.8 GB] || 12019_2FHL_3840x2160_2997_40mbps.mp4 (3840x2160) [371.2 MB] || 12019_2FHL_3840x2160_2997_20mbps.mp4 (3840x2160) [190.4 MB] ||

2015

NASA's Fermi Satellite Kicks Off a Blazar Bonanza

Go to this pageExplore how gamma-ray telescopes in space and on Earth captured an outburst of high-energy light from PKS 1441+25, a black-hole-powered galaxy more than halfway across the universe.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight CenterWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.For complete transcript, click here. || PKS_1441_still_1.png (1920x1080) [2.1 MB] || PKS_1441_still_1_print.jpg (1024x576) [45.3 KB] || PKS_1441_still_1_searchweb.png (320x180) [57.1 KB] || PKS_1441_still_1_thm.png (80x40) [7.6 KB] || PKS_1441_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.8 GB] || PKS_1441_H264_Best_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [1.5 GB] || PKS_1441_H264_Good_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [244.3 MB] || PKS_1441_Blazar_FINAL_youtube_hq.mov (1920x1080) [947.0 MB] || PKS_1441_1920x1080_4mbps.mp4 (1920x1080) [105.6 MB] || PKS_1441_Blazar_FINAL_appletv.m4v (1280x720) [126.1 MB] || PKS_1441_Blazar_FINAL_appletv.webm (1280x720) [26.3 MB] || PKS_1441_Blazar_FINAL_appletv_subtitles.m4v (1280x720) [126.2 MB] || PKS_1441_SRT_captions.en_US.srt [4.5 KB] || PKS_1441_SRT_captions.en_US.vtt [4.5 KB] || NASA_PODCAST_PKS_1441_Blazar_FINAL_ipod_sm.mp4 (320x240) [43.8 MB] ||

Fermi finds the first extragalactic gamma-ray pulsar

Go to this pageExplore Fermi's discovery of the first gamma-ray pulsar detected in a galaxy other than our own.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight CenterWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.For complete transcript, click here. || LMC_Pulsar_Multi.jpg (1920x1080) [634.9 KB] || LMC_Pulsar_Multi_print.jpg (1024x576) [191.7 KB] || LMC_Pulsar_Multi_searchweb.png (320x180) [72.6 KB] || LMC_Pulsar_Multi_thm.png (80x40) [4.8 KB] || LMC_Pulsar_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.8 GB] || LMC_Pulsar_H264_Best_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [2.6 GB] || LMC_Pulsar_H264_Good_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [668.4 MB] || G2015-084_LMC_Pulsar_Final_youtube_hq.mov (1920x1080) [1.5 GB] || LMC_Pulsar_MPEG4_1920X1080_2997.mp4 (1920x1080) [176.4 MB] || G2015-084_LMC_Pulsar_Final_appletv.m4v (1280x720) [112.5 MB] || LMC_Pulsar_Multi.tiff (1920x1080) [15.8 MB] || G2015-084_LMC_Pulsar_Final_appletv.webm (1280x720) [24.1 MB] || G2015-084_LMC_Pulsar_Final_appletv_subtitles.m4v (1280x720) [112.6 MB] || LMC_Pulsar_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [3.8 KB] || LMC_Pulsar_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [3.9 KB] || NASA_PODCAST_G2015-084_LMC_Pulsar_Final_ipod_sm.mp4 (320x240) [40.8 MB] ||

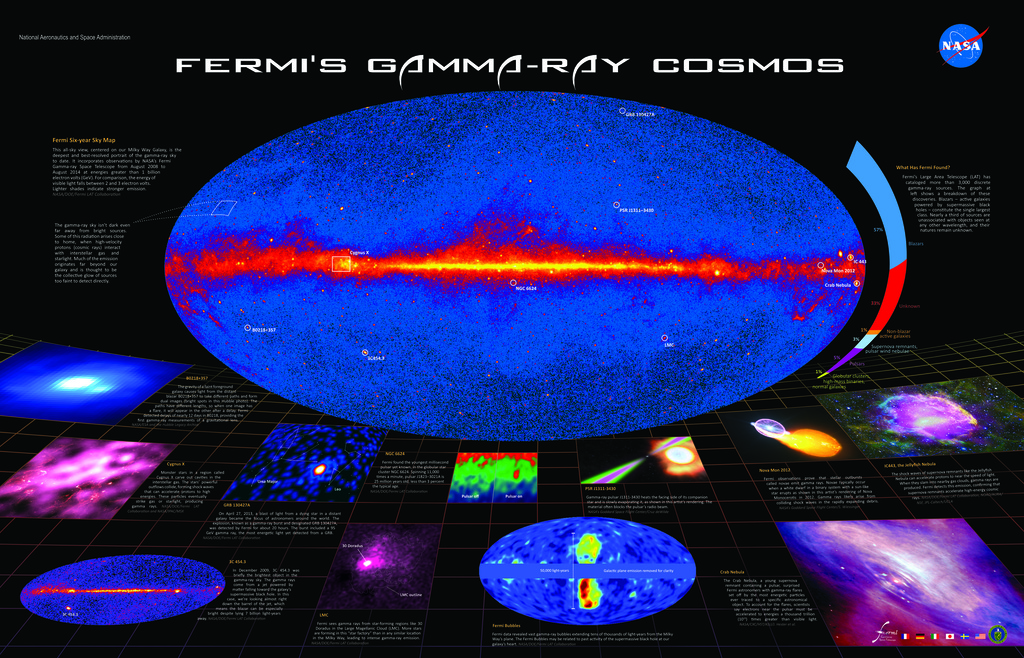

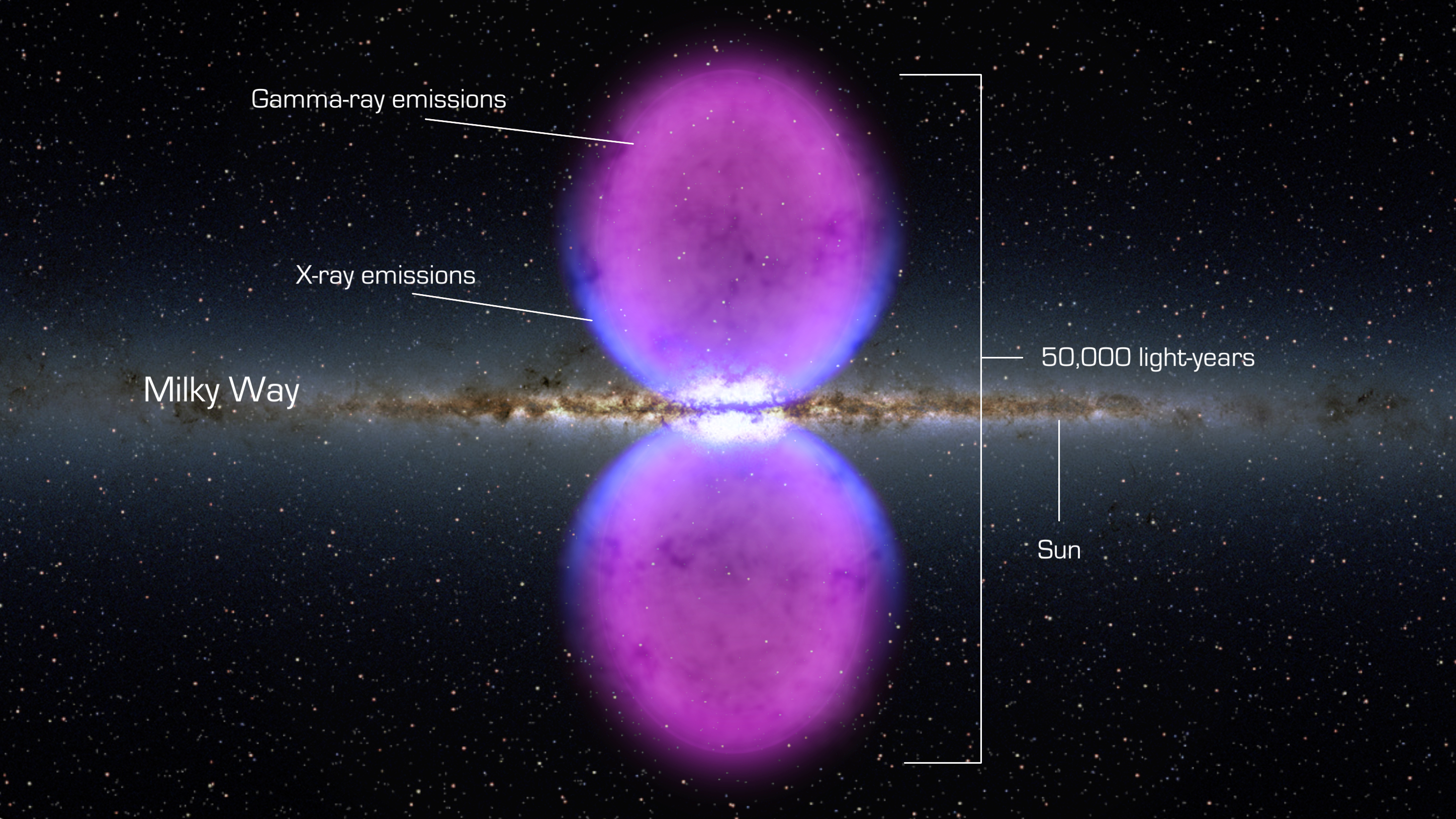

Poster: Fermi's Gamma-ray Cosmos

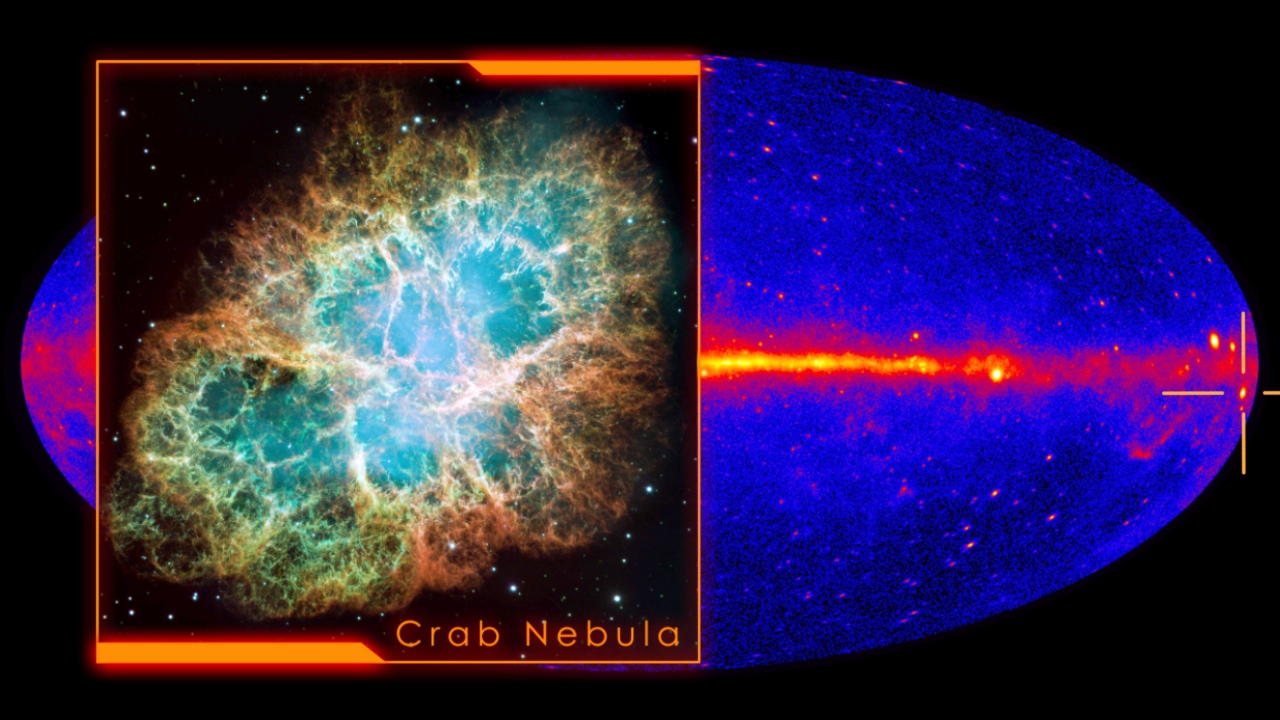

Go to this pageThis poster summarizes the career to date of NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The central image is a map of the whole sky at gamma-ray wavelengths accumulated over six years of operations. The poster also discusses other Fermi findings, including a black widow pulsar, the Fermi Bubbles rising thousands of light-years out of our galaxy's center, a giant gamma-ray flare from the Crab Nebula, and many more.The poster is available in a variety of resolutions.Credit: NASA/Fermi/Sonoma State University/A. Simonnet || FskymaPoster15-2400_print.jpg (1024x658) [1.4 MB] || FskymaPoster15.jpg (11775x7575) [24.4 MB] || FskymaPoster15-half.jpg (5888x3788) [11.0 MB] || FskymaPoster15-3840.jpg (3840x2470) [6.3 MB] || FskymaPoster15-2400.jpg (2400x1544) [3.2 MB] || FskymaPoster15-2400_searchweb.png (320x180) [490.4 KB] || FskymaPoster15-2400_thm.png (80x40) [401.9 KB] || FskymaPoster15.tif (11775x7575) [340.8 MB] ||

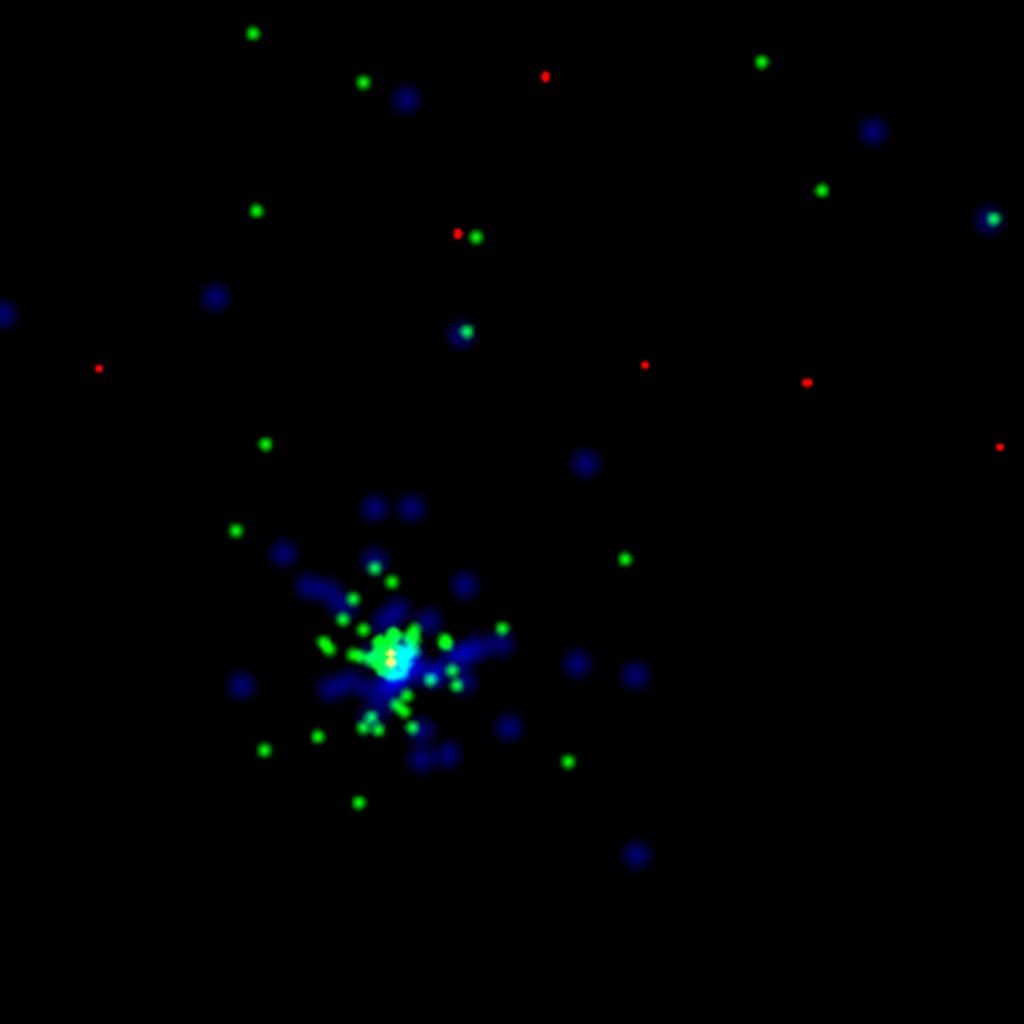

Fermi Spots a Record Flare from Blazar 3C 279

Go to this pageThis visualization shows gamma rays detected during 3C 279's big flare by the LAT instrument on NASA's Fermi satellite. The flare is an abrupt shower of "rain" that trails off toward the end of the movie. Gamma rays are represented as expanding circles reminiscent of raindrops on water. Both the maximum size of the circle and its color represent the energy of the gamma ray, with white lowest and magenta highest. The highest-energy gamma ray the LAT detected during this flare, 52 billion electron volts, arrives near the end. In a second version of the visualization, a background map shows how the LAT detects 3C 279 and other sources by accumulating high-energy photons over time (brighter squares reflect higher numbers of gamma rays). The movie starts on June 14 and ends June 17. The area shown is a region of the sky five degrees on a side and centered on the position of 3C 279. Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT CollaborationWatch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel.For complete transcript, click here. || Fermi_Rain_Still2.jpg (1920x1080) [144.1 KB] || Fermi_Rain_Still2_print.jpg (1024x576) [51.2 KB] || Fermi_Rain_Still2_searchweb.png (320x180) [24.0 KB] || Fermi_Rain_Still2_thm.png (80x40) [5.0 KB] || Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_ProRes_1920x1080_2997.mov (1920x1080) [530.3 MB] || Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_1080p.mov (1920x1080) [110.6 MB] || Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_1080.m4v (1920x1080) [81.8 MB] || WMV_Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_1280x720.wmv (1280x720) [24.3 MB] || APPLE_TV_Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_appletv.m4v (1280x720) [39.3 MB] || YOUTUBE_HQ_Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_youtube_hq.webm (1280x720) [8.5 MB] || APPLE_TV_Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_Final_appletv_subtitles.m4v (1280x720) [39.3 MB] || Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [415 bytes] || Fermi_GammaRay_Rain_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [428 bytes] ||

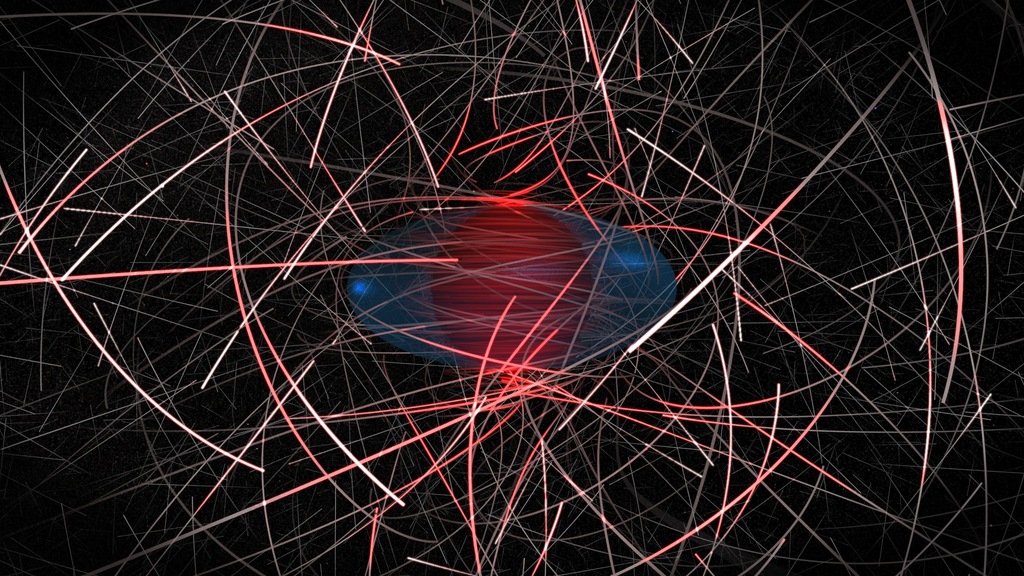

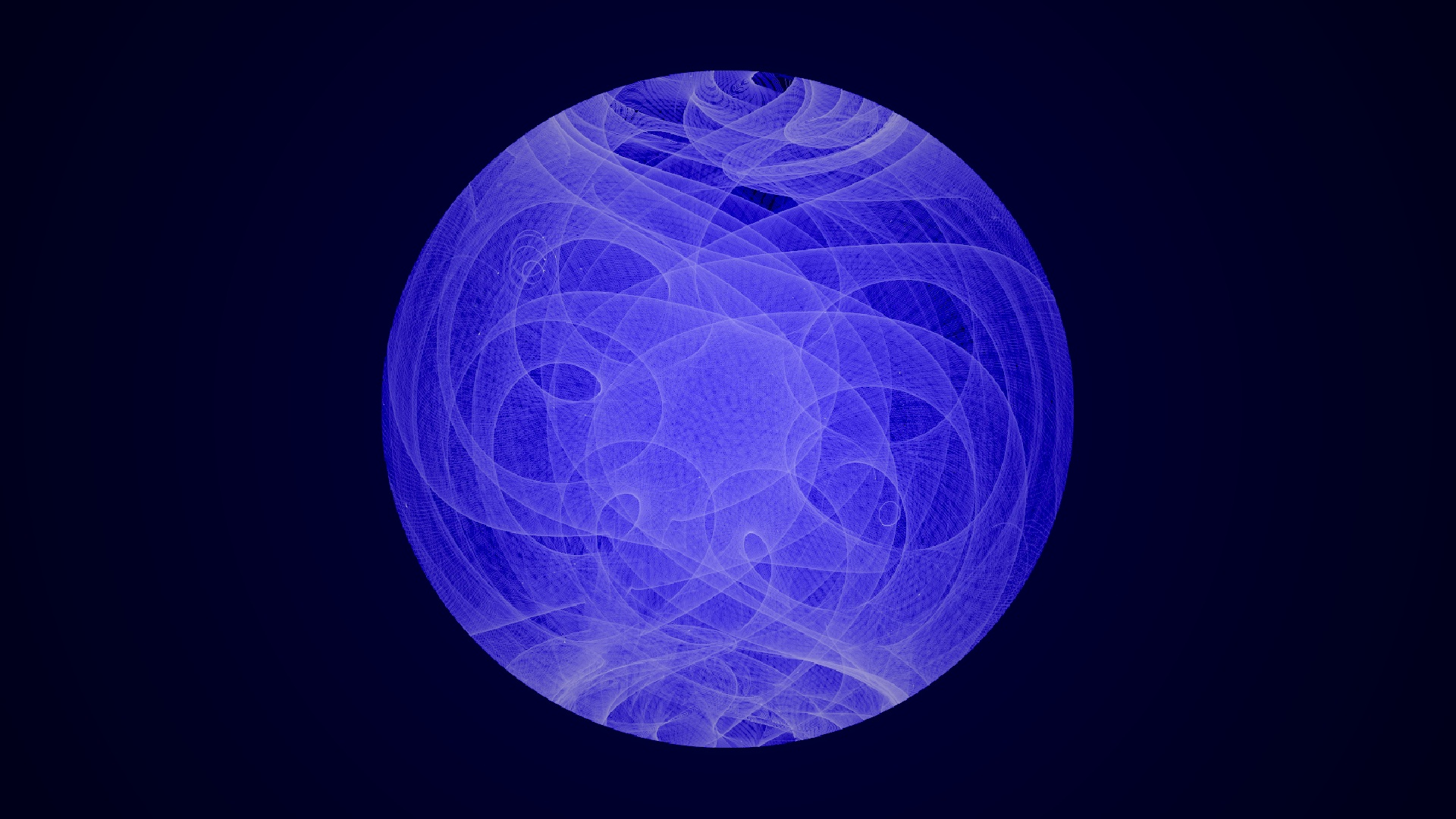

Turning Black Holes into Dark Matter Labs

Go to this sectionA new computer simulation tracking dark matter particles in the extreme gravity of a black hole shows that strong, potentially observable gamma-ray light can be produced. Detecting this emission would provide astronomers with a new tool for understanding both black holes and the nature of dark matter, an elusive substance accounting for most of the mass of the universe that neither reflects, absorbs nor emits light. Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, developed a computer simulation to follow the orbits of hundreds of millions of dark matter particles, as well as the gamma rays produced when they collide, in the vicinity of a black hole. He found that some gamma rays escaped with energies far exceeding what had been previously regarded as theoretical limits. In the simulation, dark matter takes the form of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles, or WIMPS, now widely regarded as the leading candidate class. In this model, WIMPs that crash into other WIMPs mutually annihilate and convert into gamma rays, the most energetic form of light. But these collisions are extremely rare under normal circumstances. Over the past few years, theorists have turned to black holes as dark matter concentrators, where WIMPs can be forced together in a way that increases both the rate and energies of collisions. The concept is a variant of the Penrose process, first identified in 1969 by British astrophysicist Sir Roger Penrose as a mechanism for extracting energy from a spinning black hole. The faster it spins, the greater the potential energy gain. In this process, all of the action takes place outside the black hole's event horizon, the boundary beyond which nothing can escape, in a flattened region called the ergosphere. Within the ergosphere, the black hole's rotation drags space-time along with it and everything is forced to move in the same direction at nearly speed of light. This creates a natural laboratory more extreme than any possible on Earth. Previous work indicated that the maximum gamma-ray energy from the collisional version of the Penrose process was only about 1.3 times the rest mass of the annihilating particles. In addition, only a small portion of high-energy gamma rays managed to escape the ergosphere. These results suggested that a conclusive annihilation signal might never be seen from a supermassive black hole. However, earlier work made simplifying assumptions about the locations of the highest-energy collisions. Schnittman's model instead tracks the positions and properties of hundreds of millions of randomly distributed particles as they collide and annihilate near a black hole. The new model reveals processes that produce gamma rays with much higher energies, as well as a better likelihood of escape and detection, than ever thought possible. He identified previously unrecognized trajectories where collisions produce gamma rays with a peak energy 14 times the rest mass of the annihilating particles. The simulation tells astronomers that there is an astrophysically interesting signal they may be able to detect as gamma-ray telescopes improve.

2014

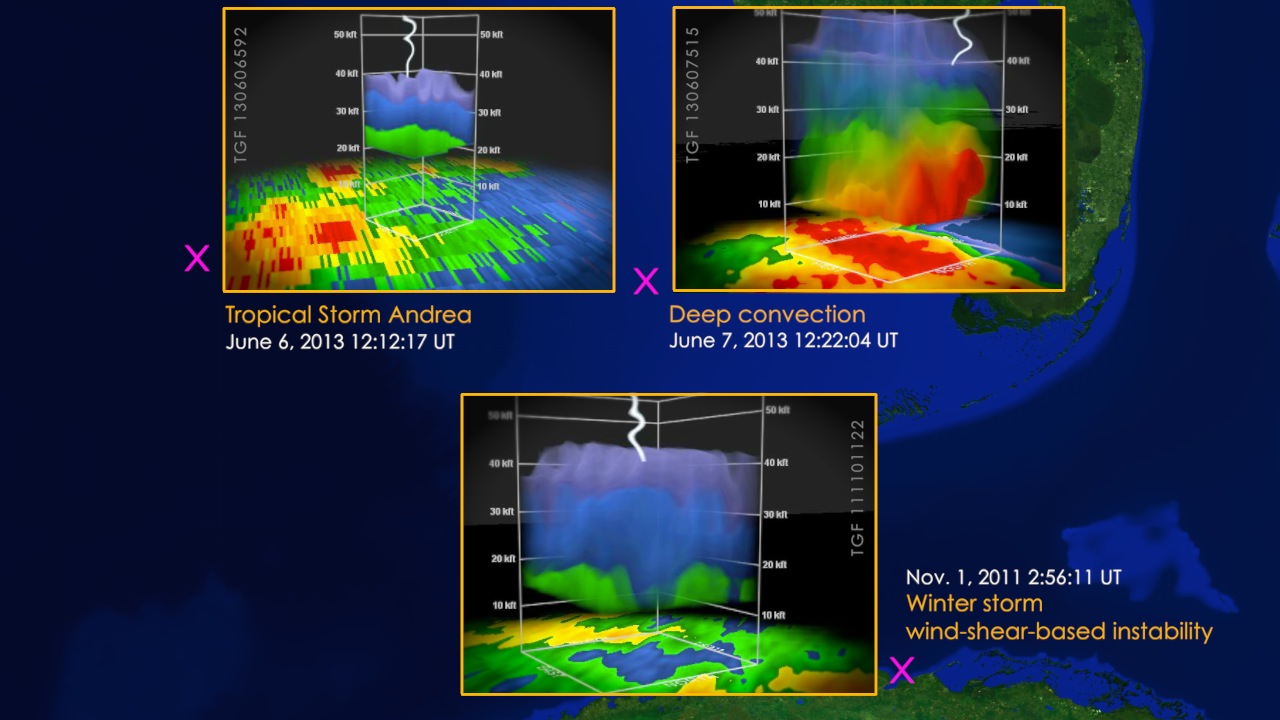

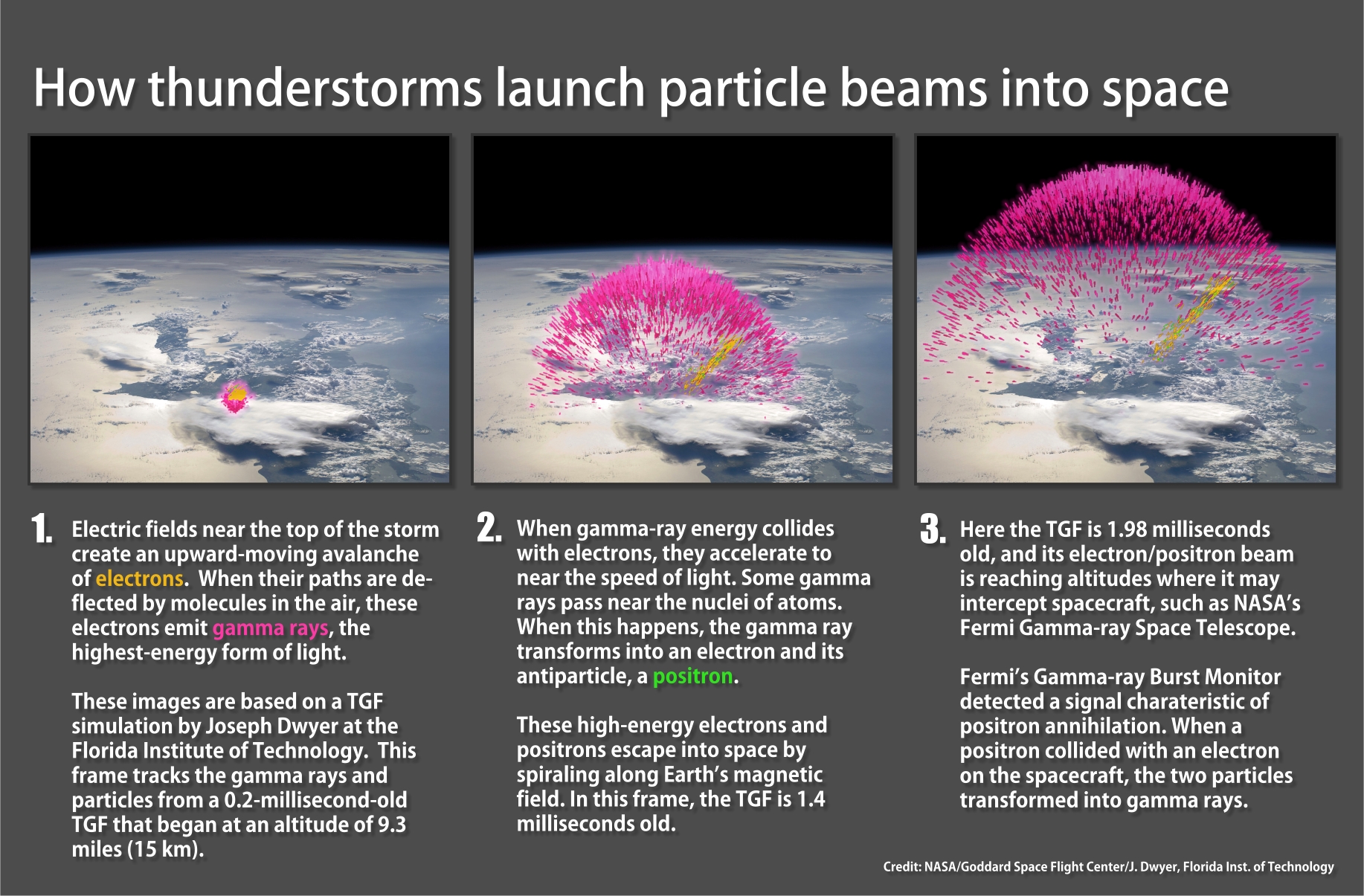

NASA's Fermi Helps Scientists Study Gamma-ray Thunderstorms

Go to this pageNew research merging Fermi data with information from ground-based radar and lightning networks shows that terrestrial gamma-ray flashes arise from an unexpected diversity of storms and may be more common than currently thought. Watch this video on the NASA Goddard YouTube channel. For complete transcript, click here. || Florida_TGF_still_print.jpg (1024x576) [115.1 KB] || Florida_TGF_still.jpg (1280x720) [169.4 KB] || Florida_TGF_still_thm.png (80x40) [8.7 KB] || Florida_TGF_still_searchweb.png (320x180) [75.0 KB] || Florida_TGF_still_web.jpg (320x180) [20.8 KB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_appletv_subtitles.m4v (960x540) [66.4 MB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_ProRes_1280x720_5994.mov (1280x720) [2.7 GB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_appletv.webm (960x540) [21.7 MB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_appletv.m4v (960x540) [66.5 MB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_MPEG4_1280X720_2997.mp4 (1280x720) [36.8 MB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_1280x720.wmv (1280x720) [62.5 MB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_H264_Good_1280x720_2997.mov (1280x720) [65.2 MB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_H264_Best_1280x720_5994.mov (1280x720) [801.8 MB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_ipod_lg.m4v (640x360) [28.5 MB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_SRT_Captions.en_US.vtt [3.7 KB] || 10278_Fermi_TGF_Radar_SRT_Captions.en_US.srt [3.7 KB] || G2014-107_Fermi_TGF_Radar_FINAL_ipod_sm.mp4 (320x240) [13.0 MB] ||

Fermi Finds Hints of Starquakes in Magnetar 'Storm'

Go to this pageAstronomers analyzing data acquired by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope during a rapid-fire "storm" of high-energy blasts in 2009 have discovered underlying signals related to seismic waves rippling throughout the host neutron star.The burst storm came from SGR J1550−5418, a neutron star with a super-strong magnetic field, also known as a magnetar. Located about 15,000 light-years away in the constellation Norma, the magnetar was quiet until October 2008, when it entered a period of eruptive activity that ended in April 2009. At times, the object produced hundreds of bursts in as little as 20 minutes, and the most intense explosions emitted more total energy than the sun does in 20 years. High-energy instruments on many spacecraft, including NASA's Swift and Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer, detected hundreds of gamma-ray and X-ray blasts.An examination of 263 individual bursts detected by Fermi's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor confirms vibrations in the frequency ranges previously only seen in rare giant flares from magnetars. Astronomers suspect these are twisting oscillations of the star where the crust and the core, bound by the magnetic field, vibrate together. In addition, a single burst showed an oscillation at a frequency never seen before and which scientists still do not understand.While there are many efforts to describe the interiors of neutron stars, scientists lack enough observational detail to choose between differing models. Neutron stars reach densities far beyond the reach of laboratories and their interiors may exceed the density of an atomic nucleus by as much as 10 times. Knowing more about how bursts shake up these stars will give theorists an important new window into understanding their internal structure.Magnetar Burst with Torsional Waves ||

Fermi Reveals Novae as a New Class of Gamma-Ray Sources

Go to this pageObservations of four stellar eruptions, called novae, by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope firmly establish that these relatively common outbursts nearly always produce gamma rays, the most energetic form of light. A nova is a sudden, short-lived brightening of an otherwise inconspicuous star caused by a thermonuclear explosion on the surface of a white dwarf, a compact star not much larger than Earth. Novae occur because a stream of gas flowing from the star continually piles up into a layer on the white dwarf's surface. This layer eventually reaches a flash point and detonates in a runaway thermonuclear explosion. Each nova releases up to 100,000 times the annual energy output of our sun. Prior to Fermi, no one suspected these outbursts were capable of producing high-energy gamma rays. Such emission, with energies millions of times greater than visible light, usually is associated with far more powerful cosmic blasts.Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) scored its first nova detection in March 2010 with an outburst of V407 Cygni. In this rare type of system, a white dwarf interacts with a red giant star more than a hundred times the size of our sun. Other members of this unusual stellar class have been observed to "go nova" every few decades.In 2012 and 2013, the LAT found three much more typical, or "classical," novae: V339 Delphini in 2013 and V1324 Scorpii and V959 Monocerotis in 2012. The outbursts occurred in comparatively common systems where a white dwarf and a sun-like star orbit each other every few hours. Astronomers estimate that between 20 and 50 novae occur each year in our galaxy. Most go undetected, their visible light obscured by intervening dust and their gamma rays dimmed by distance. All of the gamma-ray novae found so far lie between 9,000 and 15,000 light-years away, which is relatively nearby compared to our galaxy's size.One explanation for the gamma-ray emission is that the blast creates multiple shock waves, which expand into space at slightly different speeds. Faster shocks could interact with slower ones, accelerating particles to near the speed of light. These particles ultimately could produce gamma rays. ||

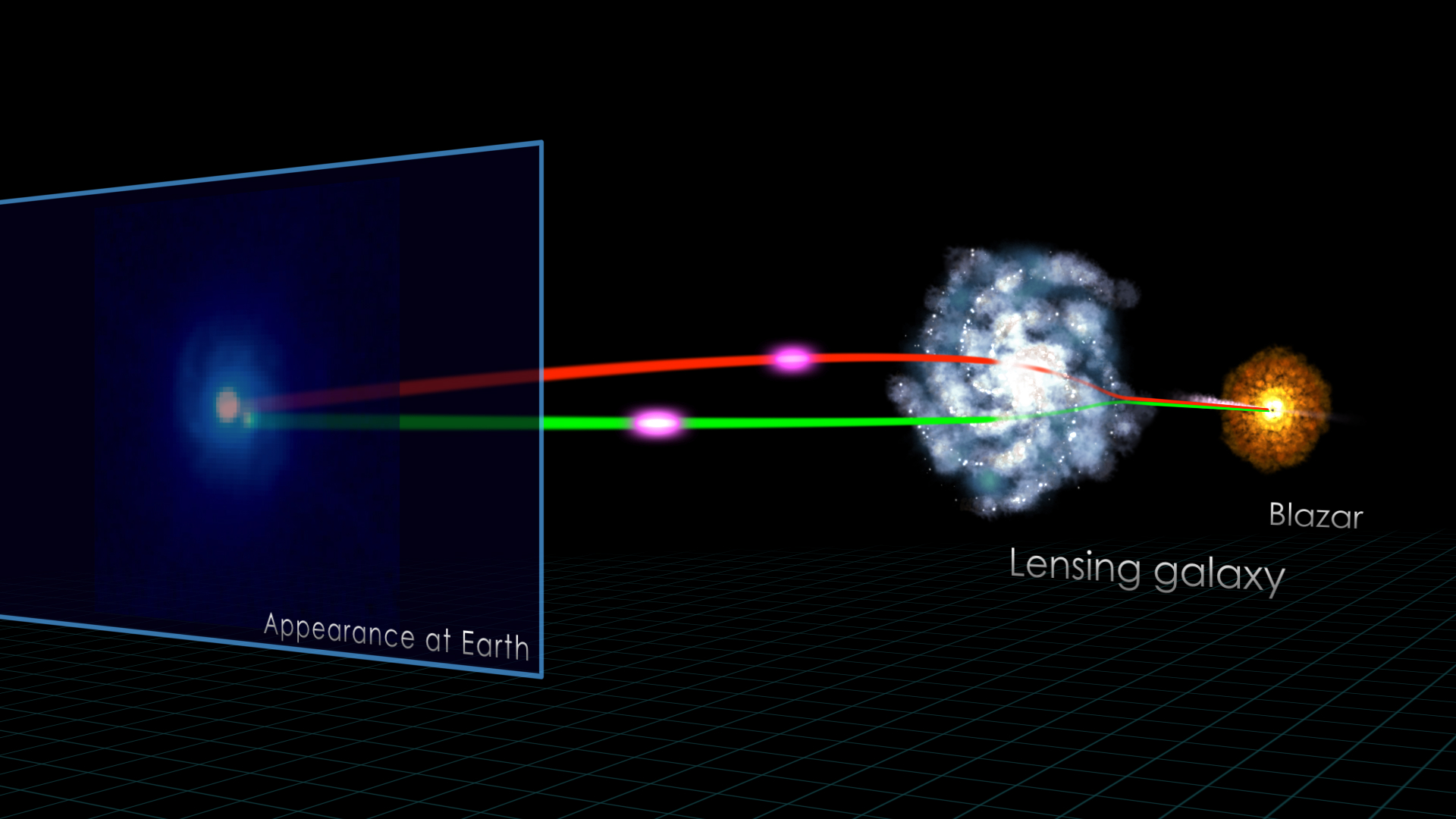

First Gamma-ray Measurement of a Gravitational Lens

Go to this pageAstronomers using NASA's Fermi observatory have made the first gamma-ray measurements of a gravitational lens, a kind of natural telescope formed when a rare cosmic alignment allows the gravity of a massive object to bend and amplify light from a more distant source.The opportunity arose in September 2012, when Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) detected a series of bright gamma-ray flares from a source known as B0218+357, located 4.35 billion light-years away in the constellation Triangulum. These powerful outbursts in a known gravitational lens provided the key to making the measurement. Astronomers classify B0218+357 as a blazar, a type of active galaxy noted for intense outbursts. At the blazar's heart is a supersized black hole with a mass millions to billions of times that of the sun. As matter spirals toward this black hole, some of it blasts outward as jets of particles traveling near the speed of light in opposite directions.Long before light from B0218+357 reaches us, it passes directly through a spiral galaxy – one much like our own – located 4.03 billion light-years away. The galaxy's gravity bends the light into different paths, so astronomers see the background blazar as dual images. But these paths aren't the same length, which means that when one image flares, there's a delay of many days before the other does.While radio and optical telescopes can resolve and monitor the individual blazar images, Fermi's LAT cannot. Instead, the Fermi team exploited the playback delay between the images. In September 2012, when the blazar's flaring activity made it the brightest gamma-ray source outside of our own galaxy, Fermi scientists took advantage of the opportunity by using a week of dedicated LAT time to hunt for delayed flares. Three episodes of flares showing playback delays of 11.46 days were found, with the strongest evidence in a sequence of flares captured during the week-long LAT observations. ||

2013

Briefing Materials: NASA Missions Explore Record-Setting Cosmic Blast

Go to this pageOn Thursday, Nov. 21, 2013, NASA held a media teleconference to discuss new findings related to a brilliant gamma-ray burst detected on April 27. Audio of the teleconference is available for download here.Related feature story: www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/nasa-sees-watershed-cosmic-blast-in-unique-detail/.Audio of Sylvia Zhu interview for a Science Podcast. Briefing Speakers Introduction: Paul Hertz, NASA Astrophysics Division Director, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C.Charles Dermer, astrophysicist, Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, D.C.Thomas Vestrand, astrophysicist, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.M.Chryssa Kouveliotou, astrophysicist, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala. Presenter 1: Charles Dermer ||

Fermi's Five-year View of the Gamma-ray Sky

Go to this pageThis all-sky view shows how the sky appears at energies greater than 1 billion electron volts (GeV) according to five years of data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. (For comparison, the energy of visible light is between 2 and 3 electron volts.) The image contains 60 months of data from Fermi's Large Area Telescope; for better angular resolution, the map shows only gamma rays converted at the front of the instrument's tracker. Brighter colors indicate brighter gamma-ray sources. The map is shown in galactic coordinates, which places the midplane of our galaxy along the center. The five-year Fermi map is available in multiple resolutions below, along with additional plots containing reference information and identifying some of the brightest sources. ||

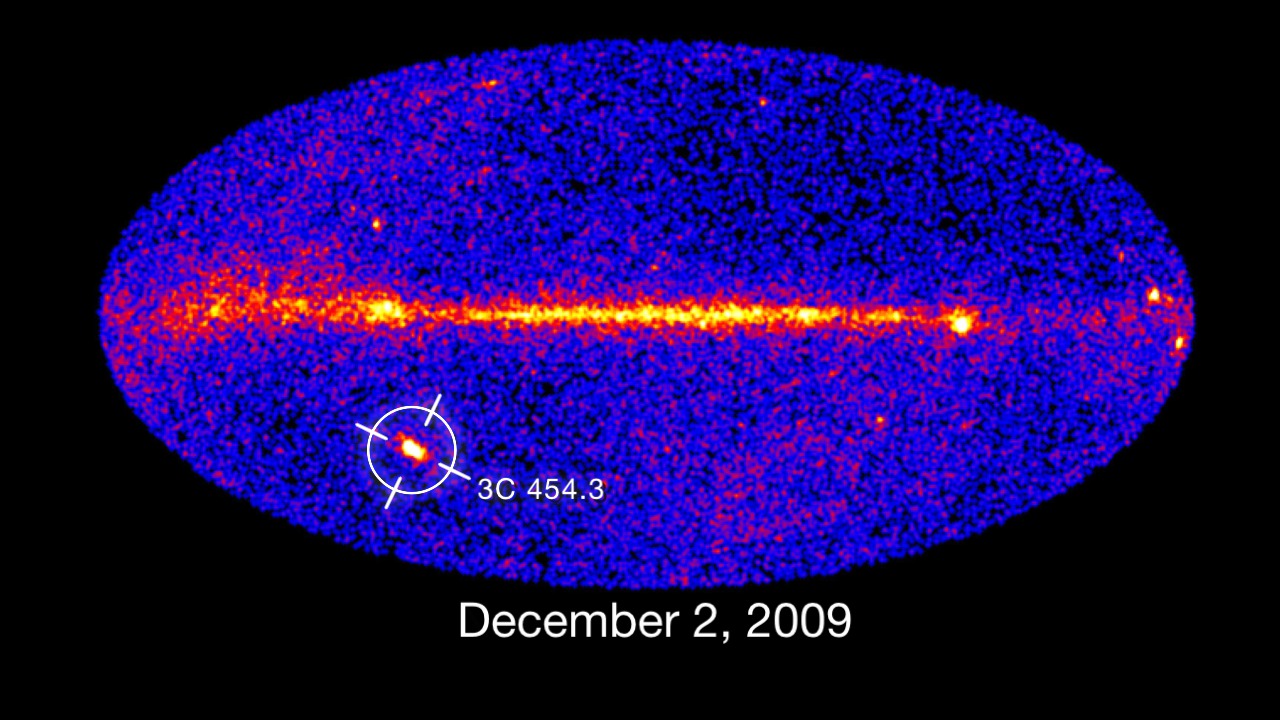

NASA's Fermi, Swift See 'Shockingly Bright' Gamma-ray Burst

Go to this pageA record-setting blast of gamma rays from a dying star in a distant galaxy has wowed astronomers around the world. The eruption, which is classified as a gamma-ray burst, or GRB, and designated GRB 130427A, produced the highest-energy light ever detected from such an event.The GRB lasted so long that a record number of telescopes on the ground were able to catch it while space-based observations were still ongoing.Just after 3:47 a.m. EDT on Saturday, April 27, Fermi's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM) triggered on an eruption of high-energy light in the constellation Leo. The burst occurred as NASA's Swift satellite was slewing between targets, which delayed its Burst Alert Telescope's detection by less than a minute. Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) recorded one gamma ray with an energy of at least 94 billion electron volts (GeV), or some 35 billion times the energy of visible light, and about three times greater than the LAT's previous record. The GeV emission from the burst lasted for hours, and it remained detectable by the LAT for the better part of a day, setting a new record for the longest gamma-ray emission from a GRB.The burst subsequently was detected in optical, infrared and radio wavelengths by ground-based observatories, based on the rapid accurate position from Swift. Astronomers quickly learned that the GRB was located about 3.6 billion light-years away, which for these events is relatively close.Gamma-ray bursts are the universe's most luminous explosions. Astronomers think most occur when massive stars run out of nuclear fuel and collapse under their own weight. As the core collapses into a black hole, jets of material shoot outward at nearly the speed of light. The jets bore all the way through the collapsing star and continue into space, where they interact with gas previously shed by the star and generate bright afterglows that fade with time. If the GRB is near enough, astronomers usually discover a supernova at the site a week or so after the outburst. This GRB is in the closest 5 percent of bursts, so ground-based observatories are monitoring its location in hopes of finding an underlying supernova. ||

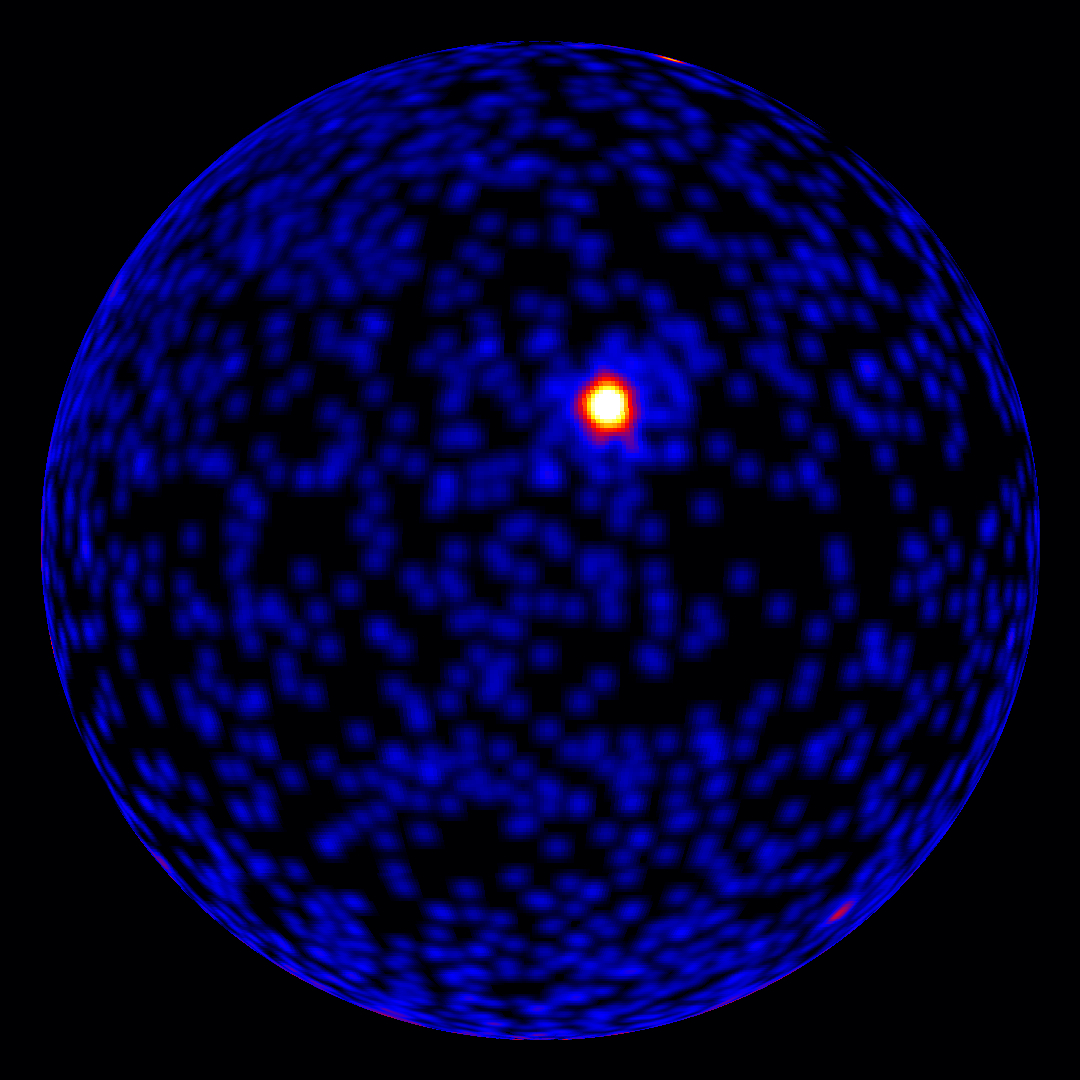

Fermi Traces a Celestial Spirograph

Go to this pageNASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope orbits our planet every 95 minutes, building up increasingly deeper views of the universe with every circuit. Its wide-eyed Large Area Telescope (LAT) sweeps across the entire sky every three hours, capturing the highest-energy form of light — gamma rays — from sources across the universe. These range from supermassive black holes billions of light-years away to intriguing objects in our own galaxy, such as X-ray binaries, supernova remnants and pulsars. Now a Fermi scientist has transformed LAT data of a famous pulsar into a mesmerizing movie that visually encapsulates the spacecraft's complex motion. Pulsars are neutron stars, the crushed cores of massive suns that destroyed themselves when they ran out of fuel, collapsed and exploded. The blast simultaneously shattered the star and compressed its core into a body as small as a city yet more massive than the sun. One pulsar, called Vela, shines especially bright for Fermi. It spins 11 times a second and is the brightest persistent source of gamma rays the LAT sees. The movie renders Vela's position in a fisheye perspective, where the middle of the pattern corresponds to the central and most sensitive portion of the LAT's field of view. The edge of the pattern is 90 degrees away from the center and well beyond what scientists regard as the effective limit of the LAT's vision. The movie tracks both Vela's position relative to the center of the LAT's field of view and the instrument's exposure of the pulsar during the first 51 months of Fermi's mission, from Aug. 4, 2008, to Nov. 15, 2012. The pattern Vela traces reflects numerous motions of the spacecraft. The first is Fermi's 95-minute orbit around Earth, but there's another, subtler motion related to it. The orbit itself also rotates, a phenomenon called precession. Similar to the wobble of an unsteady top, Fermi's orbital plane makes a slow circuit around Earth every 54 days. In order to capture the entire sky every two orbits, scientists deliberately nod the LAT in a repeating pattern from one orbit to the next. It first looks north on one orbit, south on the next, and then north again. Every few weeks, the LAT deviates from this pattern to concentrate on particularly interesting targets, such as eruptions on the sun, brief but brilliant gamma-ray bursts associated with the birth of stellar-mass black holes, and outbursts from supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. The Vela movie captures one other Fermi motion. The spacecraft rolls to keep the sun from shining on and warming up the LAT's radiators, which regulate its temperature by bleeding excess heat into space.Watch this video on YouTube. ||

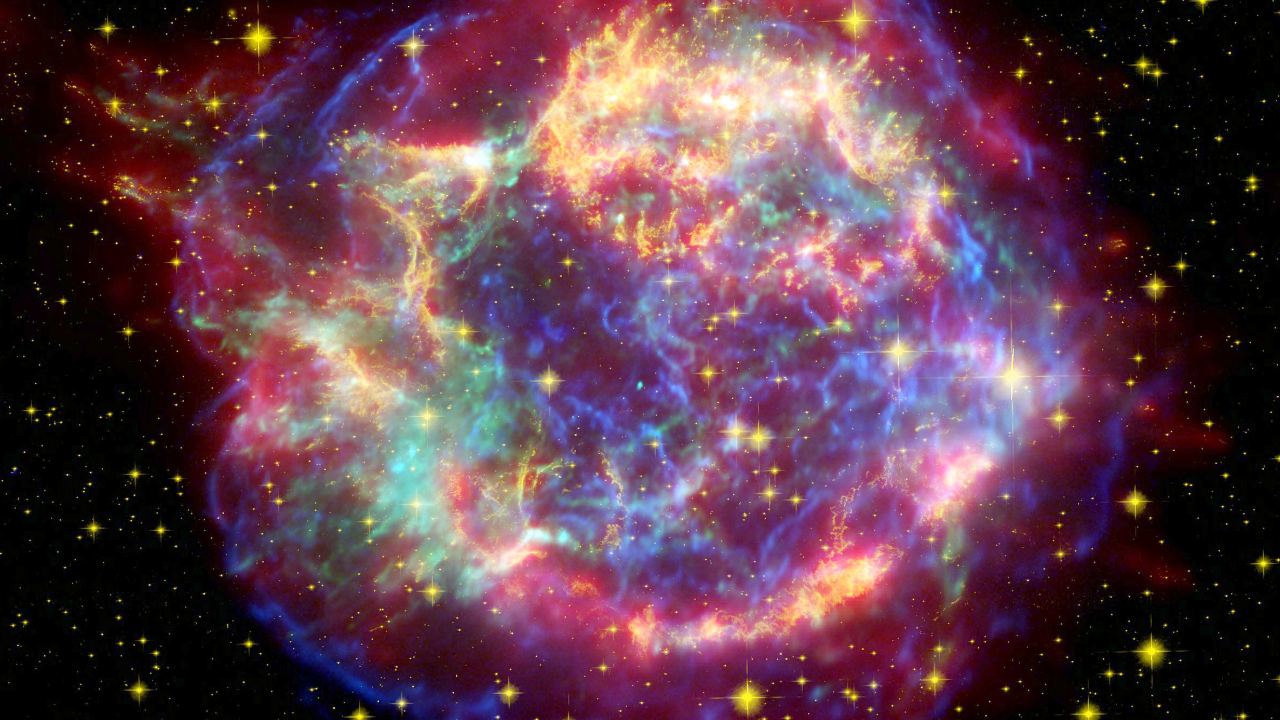

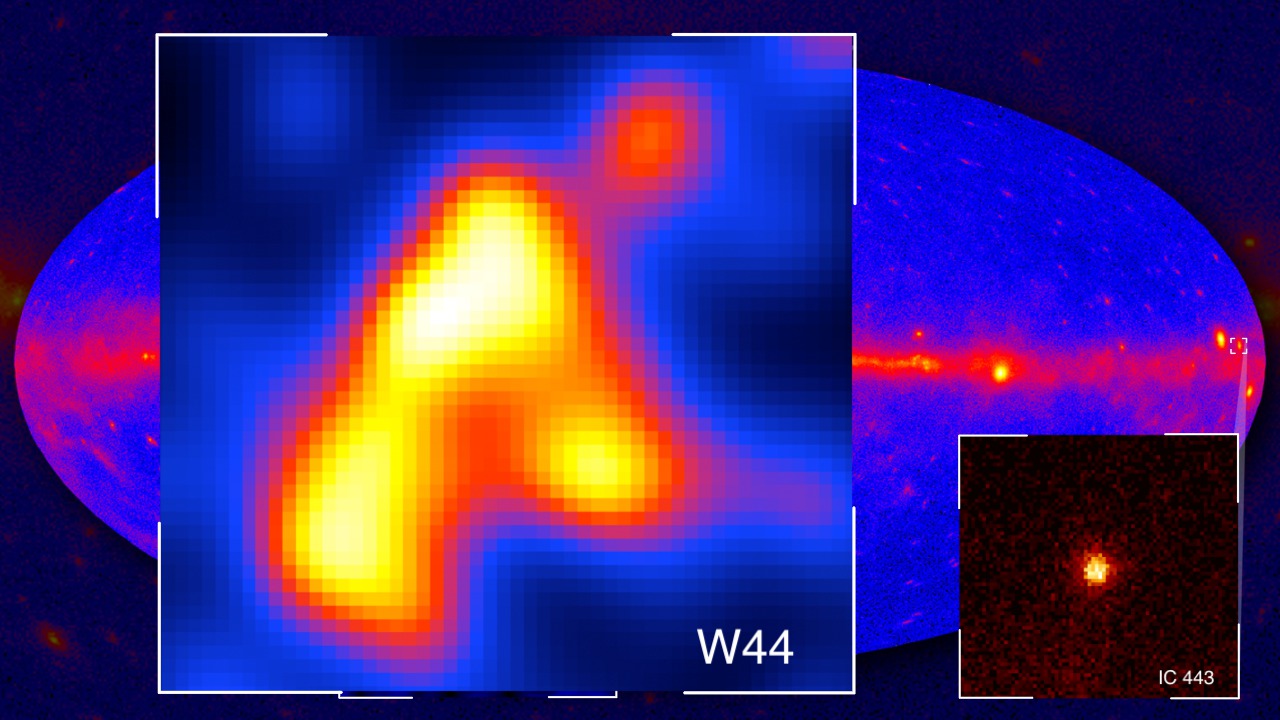

Fermi Proves Supernova Remnants Produce Cosmic Rays

Go to this pageA new study using observations from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope reveals the first clear-cut evidence that the expanding debris of exploded stars produces some of the fastest-moving matter in the universe. This discovery is a major step toward meeting one of Fermi's primary mission goals.Cosmic rays are subatomic particles that move through space at nearly the speed of light. About 90 percent of them are protons, with the remainder consisting of electrons and atomic nuclei. In their journey across the galaxy, the electrically charged particles become deflected by magnetic fields. This scrambles their paths and makes it impossible to trace their origins directly.Through a variety of mechanisms, these speedy particles can lead to the emission of gamma rays, the most powerful form of light and a signal that travels to us directly from its sources.Two supernova remnants, known as IC 443 and W44, are expanding into cold, dense clouds of interstellar gas. This material emits gamma rays when struck by high-speed particles escaping the remnants.Scientists have been unable to ascertain which particle is responsible for this emission because cosmic-ray protons and electrons give rise to gamma rays with similar energies. Now, after analyzing four years of data, Fermi scientists see a gamma-ray feature from both remnants that, like a fingerprint, proves the culprits are protons.When cosmic-ray protons smash into normal protons, they produce a short-lived particle called a neutral pion. The pion quickly decays into a pair of gamma rays. This emission falls within a specific band of energies associated with the rest mass of the neutral pion, and it declines steeply toward lower energies. Detecting this low-end cutoff is clear proof that the gamma rays arise from decaying pions formed by protons accelerated within the supernova remnants.In 1949, the Fermi telescope's namesake, physicist Enrico Fermi, suggested that the highest-energy cosmic rays were accelerated in the magnetic fields of interstellar gas clouds. In the decades that followed, astronomers showed that supernova remnants were the galaxy's best candidate sites for this process.?A charged particle trapped in a supernova remnant's magnetic field moves randomly throughout it and occasionally crosses through the explosion's leading shock wave. Each round trip through the shock ramps up the particle's speed by about 1 percent. After many crossings, the particle obtains enough energy to break free and escapes into the galaxy as a newborn cosmic ray. The Fermi discovery builds on a strong hint of neutral pion decay in W44 observed by the Italian Space Agency's AGILE gamma-ray observatory and published in late 2011.Watch this video on YouTube. ||

2012

NASA's Fermi Detects the Highest-Energy Light from a Solar Flare

Go to this sectionDuring a powerful solar blast in March, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected the highest-energy light ever associated with an eruption on the sun. The discovery heralds Fermi's new role as a solar observatory, a powerful new tool for understanding solar outbursts during the sun's maximum period of activity."For most of Fermi's four years in orbit, its Large Area Telescope (LAT) saw the sun as a faint, steady gamma-ray source thanks to the impacts of high-speed particles called cosmic rays," said Nicola Omodei, an astrophysicist at Stanford University in California. "Now we're beginning to see what the sun itself can do."A solar flare is an explosive blast of light and charged particles. The powerful March 7 flare, which earned a classification of X5.4 based on the peak intensity of its X-rays, is the strongest eruption so far observed by Fermi's LAT. The flare produced such an outpouring of gamma rays — a form of light with even greater energy than X-rays — that the sun briefly became the brightest object in the gamma-ray sky.At the flare's peak, the LAT detected gamma rays with two billion times the energy of visible light, or about 4 billion electron volts (GeV), easily setting a record for the highest-energy light ever detected during or just after a solar flare. The flux of high-energy gamma rays, defined as those with energies beyond 100 million electron volts (MeV), was 1,000 times greater than the sun's steady output. The March 7 flare also is notable for the persistence of its gamma-ray emission. Fermi's LAT detected high-energy gamma rays for about 20 hours, two and a half times longer than any event on record. Additionally, the event marks the first time a greater-than-100-MeV gamma-ray source has been localized to the sun's disk, thanks to the LAT's keen angular resolution. Flares and other eruptive solar events produce gamma rays by accelerating charged particles, which then collide with matter in the sun's atmosphere and visible surface. For instance, interactions among protons result in short-lived subatomic particles called pions, which produce high-energy gamma rays when they decay. Nuclei excited by collisions with lower-energy ions give off characteristic gamma rays as they settle down. Accelerated electrons emit gamma rays as they collide with protons and atomic nuclei.Solar eruptions are now on the rise as the sun progresses toward the peak of its roughly 11-year-long activity cycle, now expected in mid-2013.

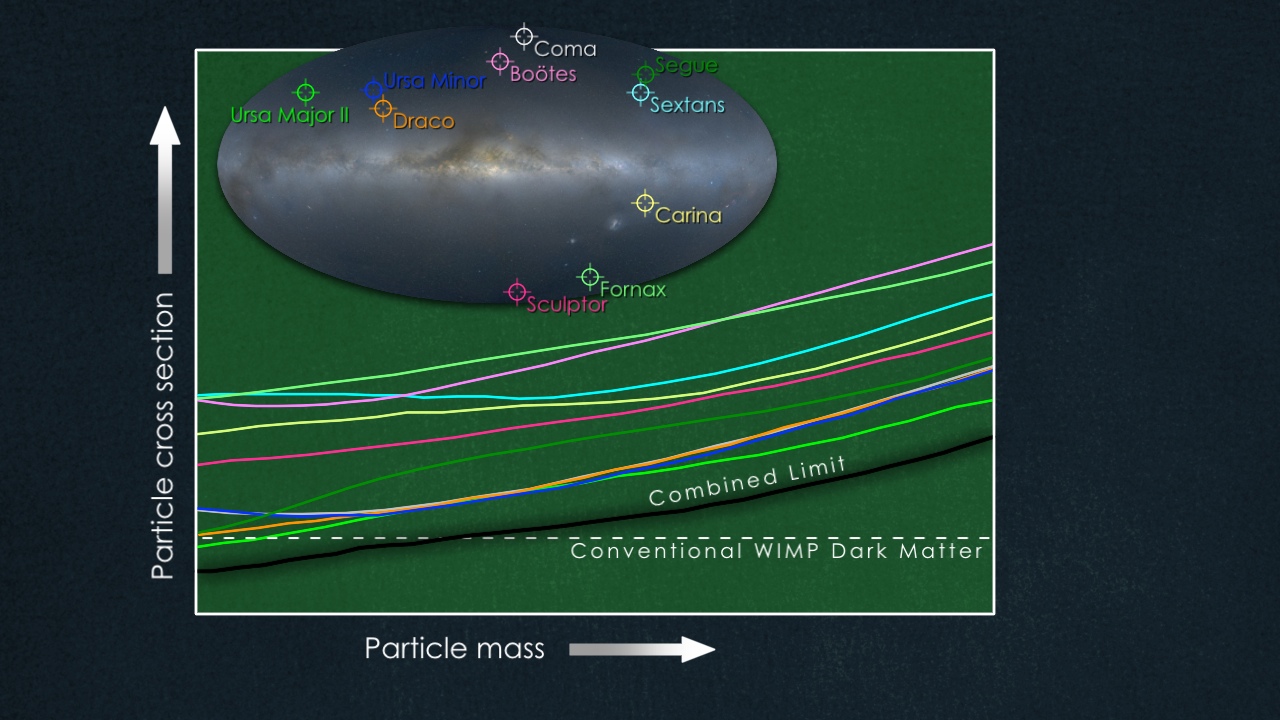

Fermi Observations of Dwarf Galaxies Provide New Insights on Dark Matter

Go to this sectionThere's more to the cosmos than meets the eye. About 80 percent of the matter in the universe is invisible to telescopes, yet its gravitational influence is manifest in the orbital speeds of stars around galaxies and in the motions of clusters of galaxies. Yet, despite decades of effort, no one knows what this "dark matter" really is. Many scientists think it's likely that the mystery will be solved with the discovery of new kinds of subatomic particles, types necessarily different from those composing atoms of the ordinary matter all around us. The search to detect and identify these particles is underway in experiments both around the globe and above it. Scientists working with data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have looked for signals from some of these hypothetical particles by zeroing in on 10 small, faint galaxies that orbit our own. Although no signals have been detected, a novel analysis technique applied to two years of data from the observatory's Large Area Telescope (LAT) has essentially eliminated these particle candidates for the first time.WIMPs, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particles, represent a favored class of dark matter candidates. Some WIMPs may mutually annihilate when pairs of them interact, a process expected to produce gamma rays — the most energetic form of light — that the LAT is designed to detect. The team examined two years of LAT-detected gamma rays with energies in the range from 200 million to 100 billion electron volts (GeV) from 10 of the roughly two dozen dwarf galaxies known to orbit the Milky Way. Instead of analyzing the results for each galaxy separately, the scientists developed a statistical technique — they call it a "joint likelihood analysis" — that evaluates all of the galaxies at once without merging the data together. No gamma-ray signal consistent with the annihilations expected from four different types of commonly considered WIMP particles was found.For the first time, the results show that WIMP candidates within a specific range of masses and interaction rates cannot be dark matter. A paper detailing these results appeared in the Dec. 9, 2011, issue of Physical Review Letters.

NASA's Fermi Space Telescope Explores New Energy Extremes

Go to this pageAfter more than three years in space, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is extending its view of the high-energy sky into a range that to date has been largely unexplored territory. Now, the Fermi team has presented its first "head count" of sources in this new realm.Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) scans the entire sky every three hours, continually deepening its portrait of the sky in gamma rays, the most extreme form of light. While the energy of visible light falls between about 2 and 3 electron volts, the LAT detects gamma rays with energies ranging from 20 million electron volts (MeV) to more than 300 billion (GeV).But at higher energies, gamma rays are few and far between. Above 10 GeV, even Fermi's LAT detects only one gamma ray every four months from some sources. The LAT's predecessor, the EGRET instrument on NASA's Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, detected only 1,500 individual gamma rays in this range during its nine-year lifetime, while the LAT detected more than 150,000 in just three years.Any object producing gamma rays at these energies is undergoing extraordinary astrophysical processes. More than half of the 496 sources in the new census are active galaxies, where matter falling into a supermassive black hole powers jets that spray out particles at nearly the speed of light. ||

2011

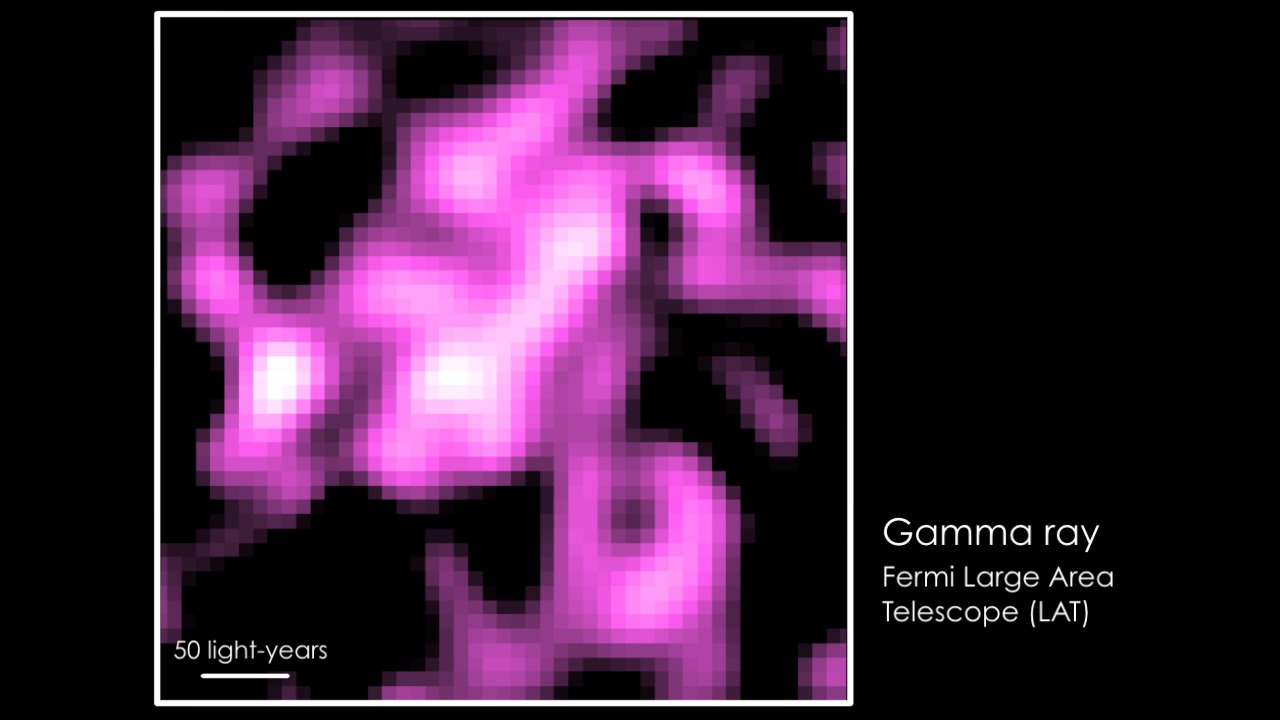

Gamma rays in the Heart of Cygnus

Go to this pageLocated in the vicinity of the second-magnitude star Gamma Cygni, the Cygnus X star-forming region was discovered as a diffuse radio source by surveys in the 1950s. Now, a study using data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope finds that the tumult of star birth and death in Cygnus X has managed to corral fast-moving particles called cosmic rays.Cosmic rays are subatomic particles — mainly protons — that move through space at nearly the speed of light. In their journey across the galaxy, the particles are deflected by magnetic fields, which scramble their paths and make it impossible to backtrack the particles to their sources. Yet when cosmic rays collide with interstellar gas, they produce gamma rays — the most energetic and penetrating form of light — that travel to us straight from the source.The Cygnus X star factory is located about 4,500 light-years away and is believed to contain enough raw material to make two million stars like our sun. Within it are many young star clusters and several sprawling groups of related O- and B-type stars, called OB associations. One, called Cygnus OB2, contains 65 O stars — the most massive, luminous and hottest type — and nearly 500 B stars. These massive stars possess intense outflows that clear out cavities in the region's gas clouds. A tangled web of shockwaves associated with this process impedes the movement of cosmic rays throughout the region. Cosmic rays striking gas nuclei or photons from starlight produce the gamma rays Fermi detects.The release on NASA.gov is here. ||

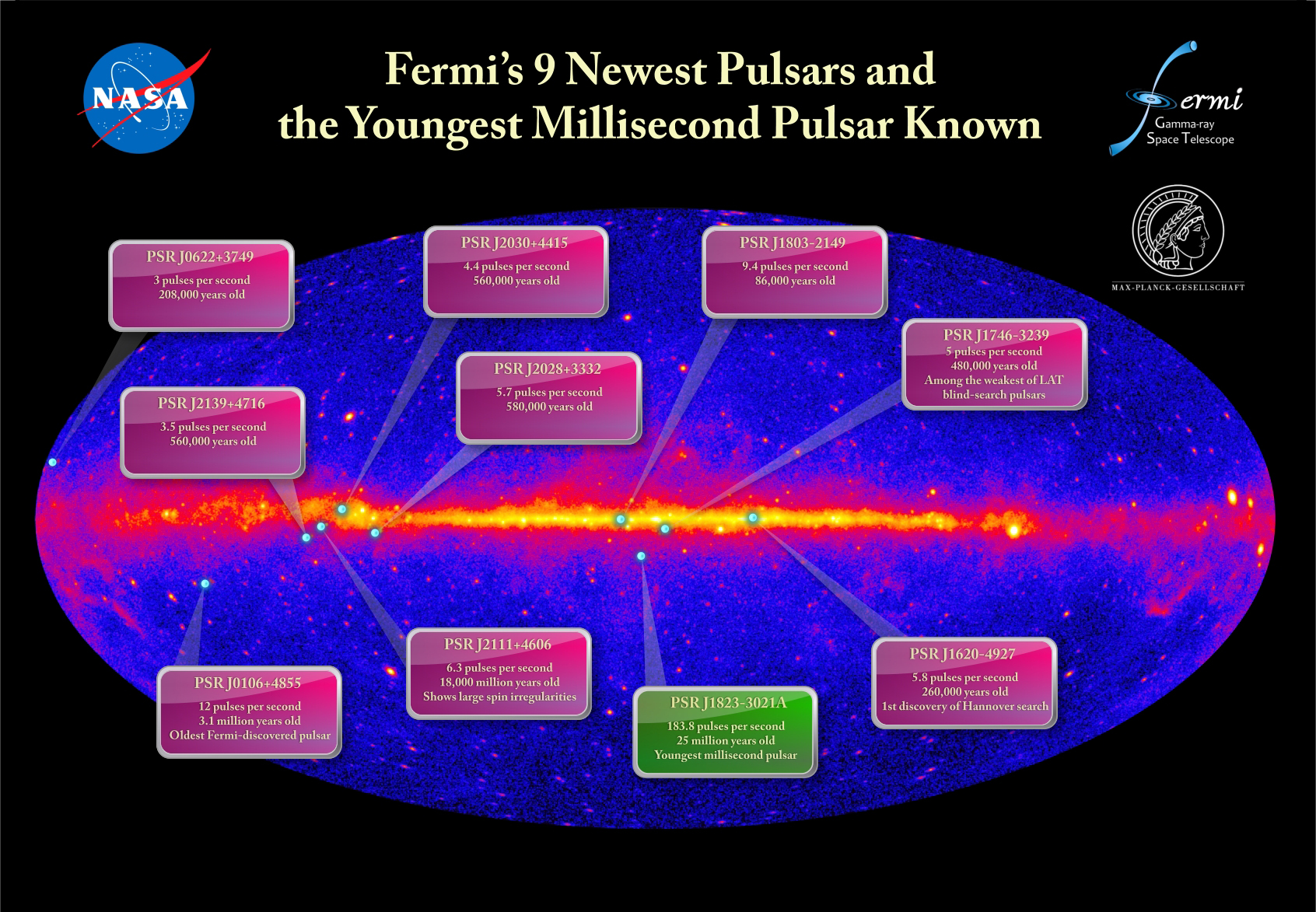

Fermi Discovers Youngest Millisecond Pulsar

Go to this pageAn international team of scientists using NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has discovered a surprisingly powerful millisecond pulsar that challenges existing theories about how these objects form. At the same time, another team has exploited improved analytical techniques to locate nine new gamma-ray pulsars in Fermi data.A pulsar, also called a neutron star, is the closest thing to a black hole astronomers can observe directly, crushing half a million times more mass than Earth into a sphere no larger than a city. This matter is so compressed that even a teaspoonful weighs as much as Mount Everest.Typically, millisecond pulsars are a billion years or more old, ages commensurate with a stellar lifetime. But in the Nov. 3 issue of Science, the Fermi team reveals a bright, energetic millisecond pulsar only 25 million years old.The object, named PSR J1823—3021A, lies within NGC 6624, a spherical assemblage of ancient stars called a globular cluster, one of about 160 similar objects that orbit our galaxy. The cluster is about 10 billion years old and lies about 27,000 light-years away toward the constellation Sagittarius."With this new batch of pulsars, Fermi now has detected more than 100, which is an exciting milestone when you consider that before Fermi's launch only seven of them were known to emit gamma rays," said Pablo Saz Parkinson, an astrophysicist at the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics, University of California Santa Cruz. ||

Fermi's Latest Gamma-ray Census Highlights Cosmic Mysteries

Go to this pageEvery three hours, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope scans the entire sky and deepens its portrait of the high-energy universe. Every year, the satellite's scientists reanalyze all of the data it has collected, exploiting updated analysis methods to tease out new sources. These relatively steady sources are in addition to the numerous transient events Fermi detects, such as gamma-ray bursts in the distant universe and flares from the sun.Earlier this year, the Fermi team released its second catalog of sources detected by the satellite's Large Area Telescope (LAT), producing an inventory of 1,873 objects shining with the highest-energy form of light. More than half of these sources are active galaxies whose supermassive black hole centers are causing the gamma-ray emissions. ||

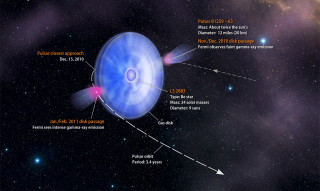

Stellar Odd Couple Makes Striking Flares

Go to this sectionEvery 3.4 years, pulsar B1259-63 dives twice through the gas disk surrounding the massive blue star it orbits. With each pass, it produces gamma rays. During the most recent event, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope observed that the pulsar's gamma-ray flare was much more intense the second time it plunged through the disk. Astronomers don't yet know why.For the B1259 binary animation, go here.

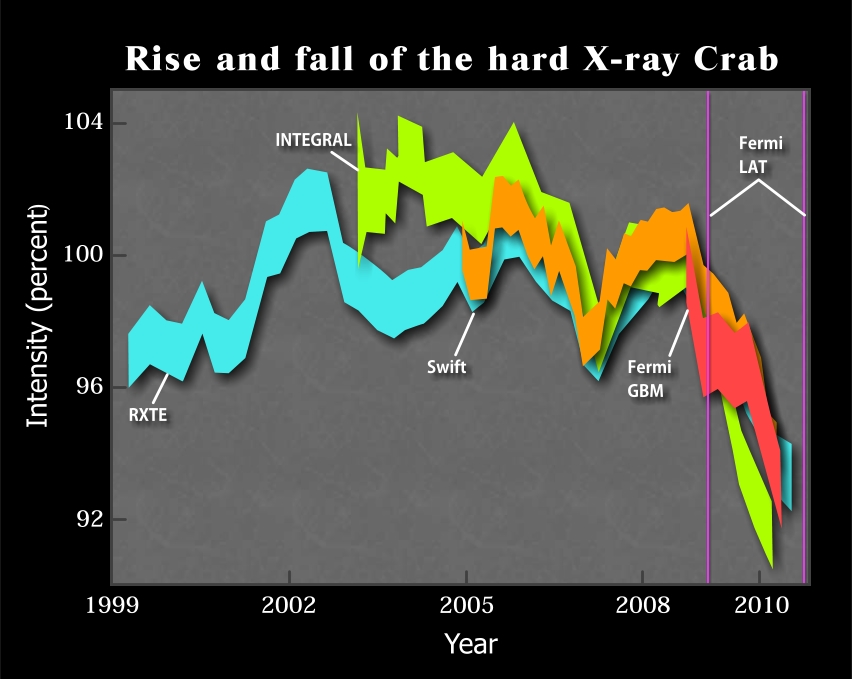

NASA's Fermi Spots 'Superflares' in the Crab Nebula

Go to this pageThe famous Crab Nebula supernova remnant has erupted in an enormous flare five times more powerful than any previously seen from the object. The outburst was first detected by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope on April 12 and lasted six days.The nebula, which is the wreckage of an exploded star whose light reached Earth in 1054, is one of the most studied objects in the sky. At the heart of an expanding gas cloud lies what's left of the original star's core, a superdense neutron star that spins 30 times a second. With each rotation, the star swings intense beams of radiation toward Earth, creating the pulsed emission characteristic of spinning neutron stars (also known as pulsars). Apart from these pulses, astrophysicists regarded the Crab Nebula to be a virtually constant source of high-energy radiation. But in January, scientists associated with several orbiting observatories — including NASA's Fermi, Swift and Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer — reported long-term brightness changes at X-ray energies.Scientists think that the flares occur as the intense magnetic field near the pulsar undergoes sudden restructuring. Such changes can accelerate particles like electrons to velocities near the speed of light. As these high-speed electrons interact with the magnetic field, they emit gamma rays in a process known as synchrotron emission.To account for the observed emission, scientists say that the electrons must have energies 100 times greater than can be achieved in any particle accelerator on Earth. This makes them the highest-energy electrons known to be associated with any cosmic source.Based on the rise and fall of gamma rays during the April outbursts, scientists estimate that the size of the emitting region must be comparable in size to the solar system. If circular, the region must be smaller than roughly twice Pluto's average distance from the sun.For more Crab Nebula media go to #10708. ||

A Flickering X-ray Candle