Fermi Proves Supernova Remnants Produce Cosmic Rays

A new study using observations from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope reveals the first clear-cut evidence that the expanding debris of exploded stars produces some of the fastest-moving matter in the universe. This discovery is a major step toward meeting one of Fermi's primary mission goals.

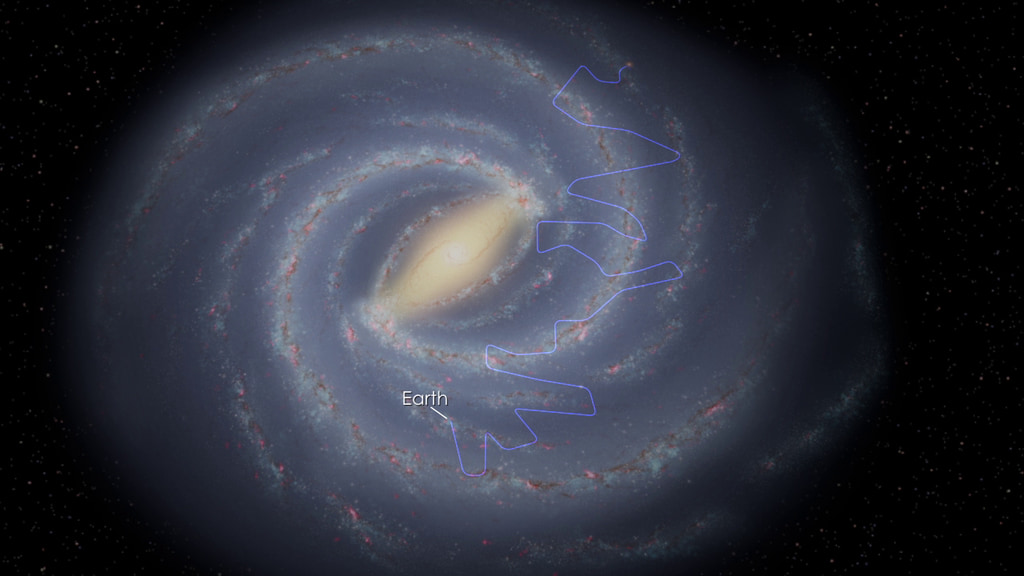

Cosmic rays are subatomic particles that move through space at nearly the speed of light. About 90 percent of them are protons, with the remainder consisting of electrons and atomic nuclei. In their journey across the galaxy, the electrically charged particles become deflected by magnetic fields. This scrambles their paths and makes it impossible to trace their origins directly.

Through a variety of mechanisms, these speedy particles can lead to the emission of gamma rays, the most powerful form of light and a signal that travels to us directly from its sources.

Two supernova remnants, known as IC 443 and W44, are expanding into cold, dense clouds of interstellar gas. This material emits gamma rays when struck by high-speed particles escaping the remnants.

Scientists have been unable to ascertain which particle is responsible for this emission because cosmic-ray protons and electrons give rise to gamma rays with similar energies. Now, after analyzing four years of data, Fermi scientists see a gamma-ray feature from both remnants that, like a fingerprint, proves the culprits are protons.

When cosmic-ray protons smash into normal protons, they produce a short-lived particle called a neutral pion. The pion quickly decays into a pair of gamma rays. This emission falls within a specific band of energies associated with the rest mass of the neutral pion, and it declines steeply toward lower energies.

Detecting this low-end cutoff is clear proof that the gamma rays arise from decaying pions formed by protons accelerated within the supernova remnants.

In 1949, the Fermi telescope's namesake, physicist Enrico Fermi, suggested that the highest-energy cosmic rays were accelerated in the magnetic fields of interstellar gas clouds. In the decades that followed, astronomers showed that supernova remnants were the galaxy's best candidate sites for this process.?

A charged particle trapped in a supernova remnant's magnetic field moves randomly throughout it and occasionally crosses through the explosion's leading shock wave. Each round trip through the shock ramps up the particle's speed by about 1 percent. After many crossings, the particle obtains enough energy to break free and escapes into the galaxy as a newborn cosmic ray.

The Fermi discovery builds on a strong hint of neutral pion decay in W44 observed by the Italian Space Agency's AGILE gamma-ray observatory and published in late 2011.

Watch this video on YouTube.

The husks of exploded stars produce some of the fastest particles in the cosmos. New findings by NASA's Fermi show that two supernova remnants accelerate protons to near the speed of light. The protons interact with nearby interstellar gas clouds, which then emit gamma rays. Short narrated video.

For complete transcript, click here.

This multiwavelength composite shows the supernova remnant IC 443, also known as the Jellyfish Nebula. Fermi GeV gamma-ray emission is shown in magenta, optical wavelengths as yellow, and infrared data from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission is shown as blue (3.4 microns), cyan (4.6 microns), green (12 microns) and red (22 microns). Cyan loops indicate where the remnant is interacting with a dense cloud of interstellar gas.

Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration, Tom Bash and John Fox/Adam Block/NOAO/AURA/NSF, JPL-Caltech/UCLA

The W44 supernova remnant is nestled within and interacting with the molecular cloud that formed its parent star. Fermi's LAT detects GeV gamma rays (magenta) produced when protons accelerated within the remnant strike the gas and produce short-lived particles called neutral pions. Radio observations (yellow) from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array near Socorro, N.M., and infrared (red) data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope reveal filamentary structures in the remnant's shell. Blue shows X-ray emission mapped by the Germany-led ROSAT mission.

Credit:

Because cosmic rays carry electric charge, their direction changes as they travel through magnetic fields. By the time the particles reach us, their paths are completely scrambled. We can't trace them back to their sources. Gamma rays travel to us straight from their sources.

Confined by a magnetic field in supernova remnants, high-energy particles move around randomly. Sometimes they cross the shock wave. With each round trip, they gain about 1 percent of their original energy. After dozens to hundreds of crossings, the particle is moving near the speed of light and is finally able to escape.

For More Information

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

-

Animators

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

- Walt Feimer (HTSI)

-

Video editor

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Narrator

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Producer

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Scientists

- Stefan Funk (KIPAC)

- Elizabeth Hays (NASA/GSFC)

-

Science writer

- Francis Reddy (University of Maryland College Park)

-

Writer

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Graphics

- Francis Reddy (University of Maryland College Park)

Release date

This page was originally published on Thursday, February 14, 2013.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 3, 2023 at 1:52 PM EDT.

Missions

This page is related to the following missions:Series

This page can be found in the following series:Tapes

The media on this page originally appeared on the following tapes:-

Fermi SNR Pion

(ID: 2013005)

Friday, February 15, 2013 at 5:00AM

Produced by - Robert Crippen (NASA)