When Fermi Dodged a 1.5-ton Bullet

NASA scientists don't often learn that their spacecraft is at risk of crashing into another satellite. But when Julie McEnery, the project scientist for NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, checked her email on March 29, 2012, she found herself facing this precise situation.

While Fermi is in fine shape today, continuing its mission to map the highest-energy light in the universe, the story of how it sidestepped a potential disaster offers a glimpse at an underappreciated aspect of managing a space mission: orbital traffic control.

As McEnery worked through her inbox, an automatically generated report arrived from NASA's Robotic Conjunction Assessment Risk Analysis (CARA) team based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. On scanning the document, she discovered that Fermi was just one week away from an unusually close encounter with Cosmos 1805, a dead Cold-War era spy satellite.

The two objects, speeding around Earth at thousands of miles an hour in nearly perpendicular orbits, were expected to miss each other by a mere 700 feet.

Although the forecast indicated a close call, satellite operators have learned the hard way that they can't be too careful. The uncertainties in predicting spacecraft positions a week into the future can be much larger than the distances forecast for their closest approach.

With a speed relative to Fermi of 27,000 mph, a direct hit by the 3,100-pound Cosmos 1805 would release as much energy as two and a half tons of high explosives, destroying both spacecraft.

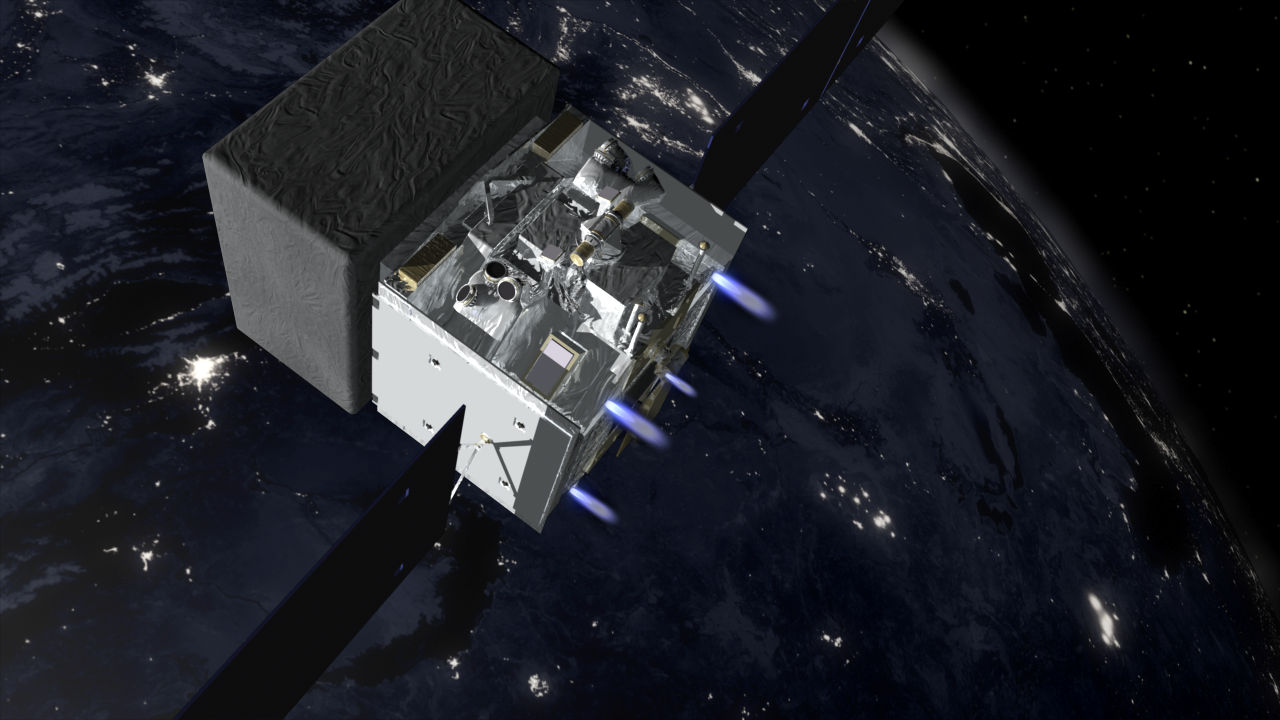

The update on Friday, March 30, indicated that the satellites would occupy the same point in space within 30 milliseconds of each other. Fermi would have to move out of the way if the threat failed to recede. Because Fermi's thrusters were designed to de-orbit the satellite at the end of its mission, they had never before been used or tested, adding a new source of anxiety for the team.

By Tuesday, April 3, the close approach was certain, and all plans were in place for firing Fermi's thrusters. The maneuver was performed by the spacecraft based on previously developed procedures. Fermi fired all thrusters for one second and was back doing science within the hour.

Watch this video on YouTube.

Animation of Earth with near-Earth orbital debris. The debris field is real data from the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office. Now includes UHD/4k version.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/JSC

Shorter version of animation showing Earth with near-Earth orbital debris. The debris field is real data from the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/JSC

For More Information

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

-

Animators

- Chris Meaney (HTSI)

- Walt Feimer (HTSI)

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Video editor

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Interviewees

- Julie McEnery (NASA/GSFC)

- Eric Stoneking (NASA/GSFC)

-

Producer

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Videographers

- Rob Andreoli (Advocates in Manpower Management, Inc.)

- John Caldwell (Advocates in Manpower Management, Inc.)

-

Writers

- Francis Reddy (Syneren Technologies)

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

Release date

This page was originally published on Tuesday, April 30, 2013.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 3, 2023 at 1:52 PM EDT.

Missions

This page is related to the following missions:Series

This page can be found in the following series:Tapes

The media on this page originally appeared on the following tapes:-

Fermi Collision Avoidance

(ID: 2012083)

Friday, April 19, 2013 at 4:00AM

Produced by - Robert Crippen (NASA)