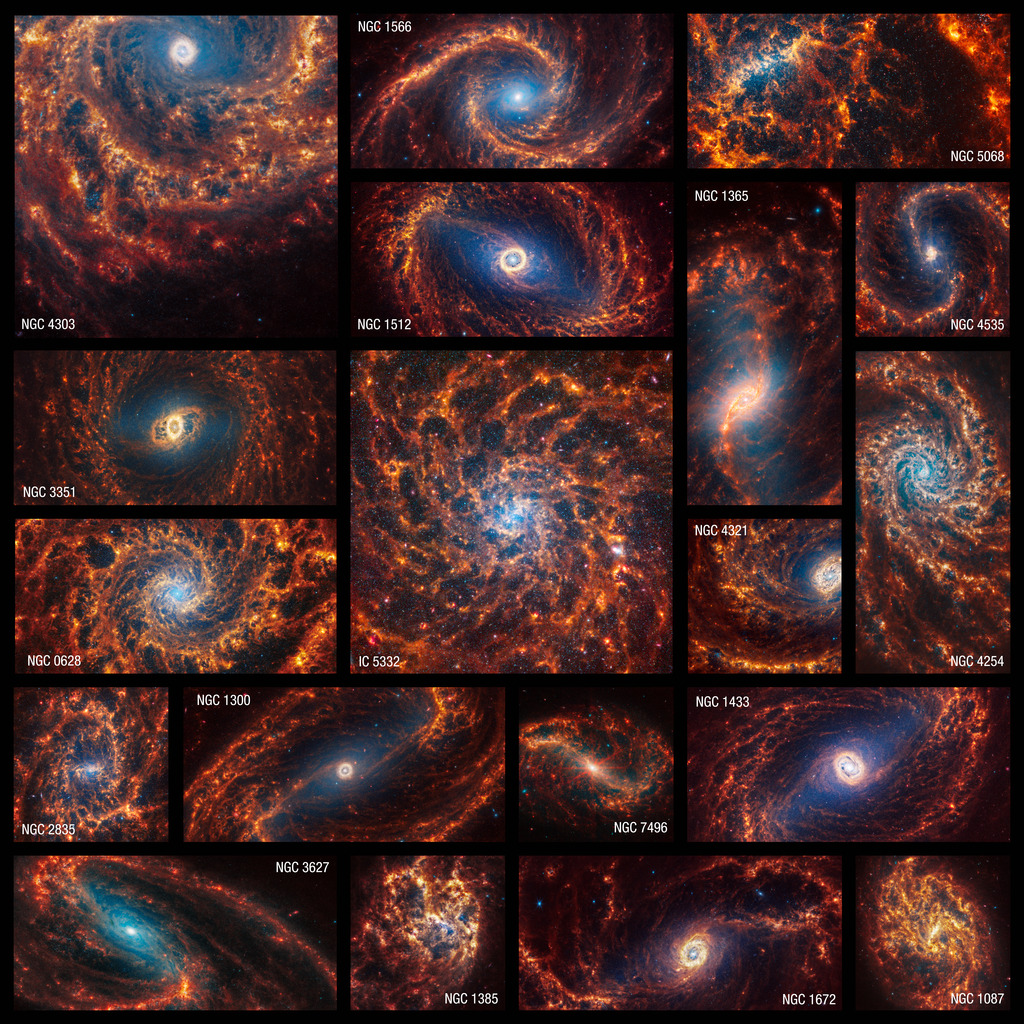

Webb and Hubble's Views of Spiral Galaxy NGC 628

animated comparison

Face-on spiral galaxy, NGC 628, is split diagonally in this image: The James Webb Space Telescope’s observations appear at top left, and the Hubble Space Telescope’s on bottom right. Webb and Hubble’s images show a striking contrast, an inverse of darkness and light. Why? Webb’s observations combine near- and mid-infrared light and Hubble’s showcase visible light. Dust absorbs ultraviolet and visible light, and then re-emits it in the infrared. In Webb's images, we see dust glowing in infrared light. In Hubble’s images, dark regions are where starlight is absorbed by dust.

The individual Webb and Hubble images are available for download using the links on the left side of this page.

Color Decoder

Gas and Dust

In Webb’s high-resolution infrared images, the gas and dust stand out in stark shades of orange and red, and show finer spiral shapes with the appearance of jagged edges, though these areas are still diffuse.

In Hubble’s images, the gas and dust show up as hazy dark brown lanes, following the same spiral shapes. Its images are about the same resolution as Webb’s, but the gas and dust obscure a lot of the smaller-scale star formation.

Bright Central Spikes

Bright red diffraction spikes at a galaxy’s core in a Webb image can be a “calling card” of an active supermassive black hole, as seen in galaxy NGC 7496. Not all oversized diffraction spikes at galaxies’ cores are caused by black holes, though. Sometimes, they appear when a slew of very bright, centrally located star clusters are in the central region of Webb’s image.

In Hubble’s images, the galaxies’ cores are not as bright so these spikes are absent. Diffraction spikes only appear when the source is extremely bright and compact.

Older Stars

Sometimes, the central region in Webb’s image has a blue glow. This is a marker of high concentrations of older stars. Webb’s infrared observations allow us to see through the gas and dust to identify these older stars. The light these old stars emit are some of the shortest infrared wavelengths in Webb’s images, which is why they are assigned blue. (Read more about how color is precisely applied to Webb’s images.)

In comparison, the cores of Hubble’s image may appear yellower, washing the central region in a soft glow and fully obscuring individual points of light. Hazy brown dust lanes may also cover part of this area. In Hubble’s images, older stars are emitting some of the longest wavelengths of visible light Hubble captures, which is why the color assignments are different. (Compare the wavelengths of light Hubble and Webb observe.)

Younger Stars

In Webb’s image, the newly fully formed stars also appear blue along the galaxies’ spiral arms. Those blue stars have blown away the gas and dust that immediately surrounded them. The farther away they are from the core, the more likely stars are to be younger. Orange stars, likely seen in groups in these images, are even younger: They are still encased in their cocoons of gas and dust, allowing them to continue forming.

In Hubble’s images, younger stars pop out in blue and purple – and appear almost everywhere. In contrast, the older stars near the center of the galaxy appear yellowish.

Star-Forming Regions

Look for knots of bright red and orange in Webb’s image. These are especially easy to identify toward the outer edges of the galaxy’s spiral arms. These are regions of star formation, and mid-infrared light highlights the gas and dust that are a huge part of the mix, since they are primary ingredients for stars that are actively forming.

In Hubble’s images, star-forming regions are clusters of bright blue and purple, or sometimes red and pink as hot stars energize nearby hydrogen gas.

Background Galaxies

Webb’s image includes distant galaxies that are located well behind the tightly cropped foreground galaxy. Look for bright blue and pink disks, some seen edge-on, like a plate with a central sphere. Redder galaxies are more distant.

In Hubble’s view, distant galaxies are often light orange if they are slightly closer. Like in Webb's image, those that are deeper red are also more distant.

Galaxy NGC 628 was observed as part of the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) program, a large project that includes observations from several space- and ground-based telescopes of many galaxies to help researchers study all phases of the star formation cycle, from the formation of stars within dusty gas clouds to the energy released in the process that creates the intricate structures revealed by Webb’s new images.

NGC 628 is 32 million light-years away in the constellation Pisces.

Credits

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Janice Lee (STScI), Thomas Williams (Oxford), PHANGS Team

Comparison still

Webb Space Telescope still

Hubble Space Telescope still

For More Information

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, the PHANGS (Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS) Team

-

Animator

- Amy Moran (Global Science and Technology, Inc.)

-

Scientists

- Janice Lee (STScI)

- Thomas Williams (Oxford)

- Elizabeth Wheatley (STScI)

Release date

This page was originally published on Thursday, June 13, 2024.

This page was last updated on Monday, March 10, 2025 at 12:29 AM EDT.